What 600+ women told us about working in healthcare in 2018

It has been more than four decades since the term “sexual harassment” entered our lexicon (during the first lawsuit of its kind, the Carmita Wood case). Coining this term allowed women who experienced it to not only better understand what was happening to them in context of a common problem, but also gave them a language to break free from isolated, individual experiences. Only when we have the vocabulary to talk about a problem can we address it and change the issue. In the same way, the #MeToo movement has paved way for a resurgence in collective empowerment. The hashtag has been leveraged as a power-of-the-masses vehicle to bring light to a systemic problem.

We have been writing about the state of women in healthcare since 2012, but something is different this year. A palpable movement (#MeToo, as well as #TimesUp) has focused attention on this enormous problem previously only whispered about in break rooms. Although the packaging of this issue has changed, the goal remains the same: to fight gender discrimination. And we’re on board.

Healthcare has not been immune from the negative impacts of gender discrimination. In fact, #MeTooMedicine has become its own phenomenon where women health workers have bravely shared stories of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. In 2012, physician assistant Ani Chopourian was awarded the largest single-plaintiff employment verdict of the time ($168M) after her case, Chopourian v. Catholic Healthcare West, revealed she was tormented and sexually harassed by medical staff at her hospital (and then terminated for filing complaints to the hospital’s HR department). Other gender discrimination cases in healthcare have included: Novartis, which settled and paid $152.5M in a gender-discrimination class action suit in 2010, and had another $8M settlement for a similar suit in 2016; Salk Institute for Biological Studies, which was sued last year by senior women scientists for systemic sexism; Boston Scientific, which was sued for $50M in 2015 for allegedly discriminating against female sales representatives; OrbiMed, whose founder stepped down after a barrage of sexual harassment allegations in 2017; Kansas University Hospital, which was sued in 2015 by a former cafeteria worker who said the HR department did not take necessary steps after she was sexually harassed by a coworker; Allergan, which paid a $4M settlement for sex discrimination charges in 2017; and University of Connecticut Health Center, which was found liable in 2017 for a sexual harassment case.

When women are treated as inferior to men in the workplace, they face challenges ranging from wage discrimination to stunted career advancement to sexual objectification and harassment. While we slowly chip away at the overt actions that plagued the Mad Men generation, we are still faced with a more covert discrimination that’s harder to identify, name, and resolve.

Gender discrimination—in any of its ugly forms—is not just unjust, it’s bad for business. To better understand the underlying sentiments and experience of women working in healthcare we put out an annual survey to our network. This year, we received more responses than ever before. Here’s what we learned from 6351 women across healthcare.

Women remain pessimistic in 2018

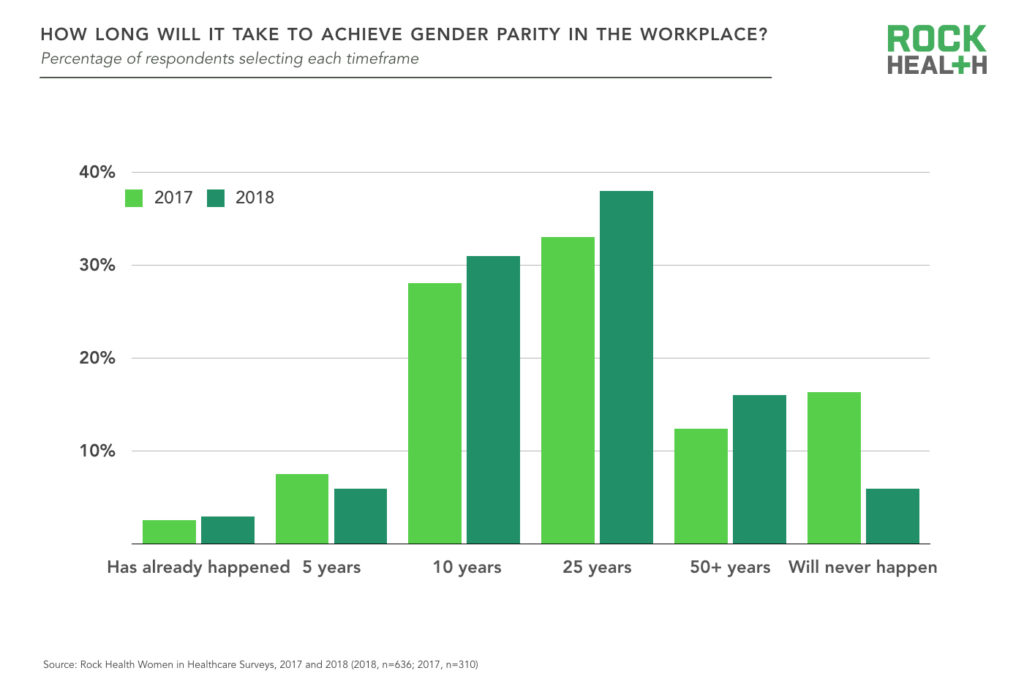

Approximately 55% of respondents believe it will take 25+ years to achieve gender parity in the workplace (up from 45% in 2017). Fewer (just 5%) say it will happen in the next five years (compared to 8% in 2017). Women taking our survey continue to be pessimistic about how long it will take to reach parity (although this year, fewer say parity will never happen).

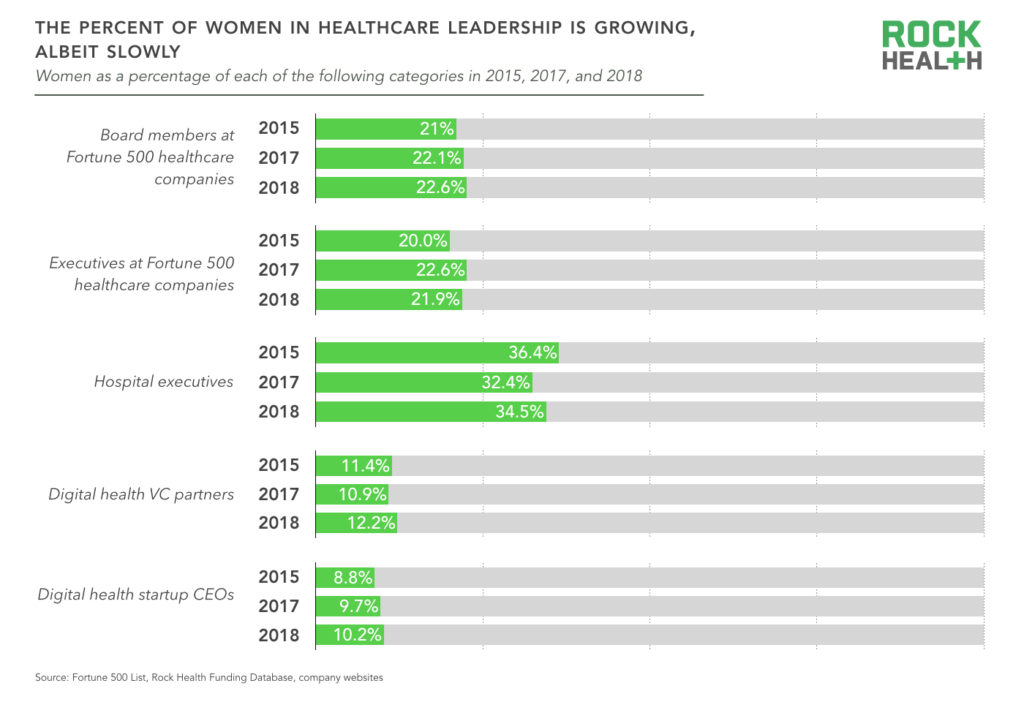

Perhaps pessimism comes from the sluggish pace of change. The percentage of women on Fortune 500 healthcare executive teams and boards has been nearly flat since 2015, hovering around 22%. The percent of women executives at hospitals has remained around a third of all executives. Women in the startup world have also seen little change: the percent of women CEOs of funded digital health startups, as well as the percent of women VC partners, stands around 10-12%. Things just aren’t moving fast enough.

Gender inequality is alive and well. Let’s finally act on it!

Survey respondent from Los Angeles, CA

Source: Fierce CEO

Size matters

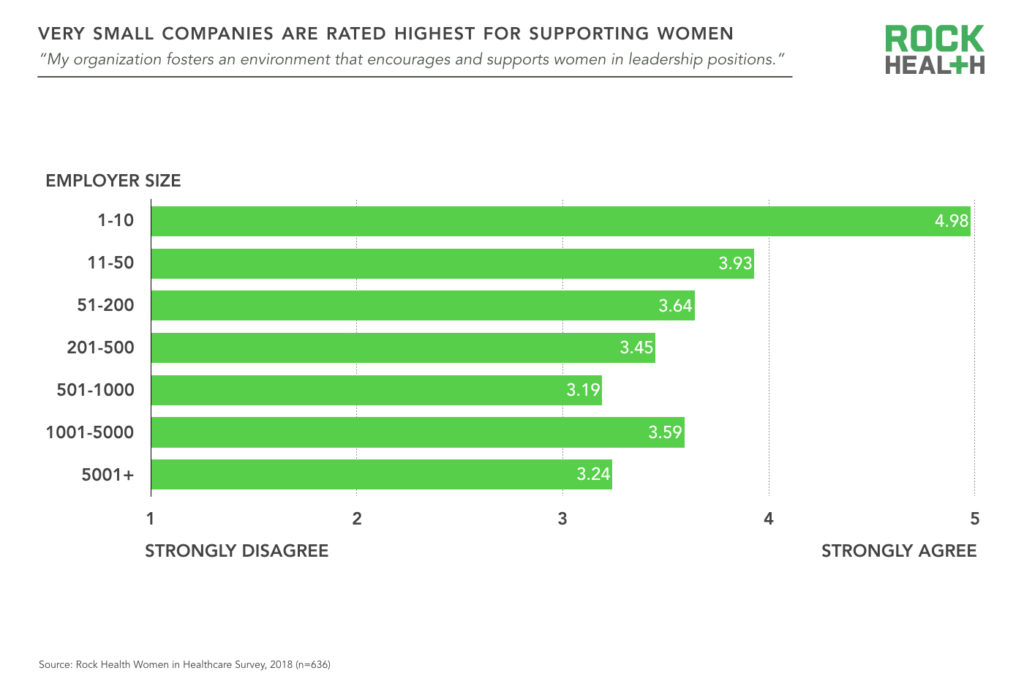

Women in smaller companies are more likely than those at larger companies to agree their employer fosters a supportive environment for women in leadership positions. Respondents working for very small companies (under 10 employees) are the most likely to strongly agree that their employer supports women leaders. The agreement decreases as company size increases until we reach over 1,000 employees—perhaps because the smallest companies can closely control company culture, and larger companies can afford to build out robust diversity programs.

Women working in smaller companies also say their employer better supports general career development. On a scale of 1-10, with 10 being the best, women working in companies under 10 employees give their employers the highest rating: 8.3 out of 10. Conversely, in companies with over 1,000 people, ratings drop, as does the average percentage of women executives (21% on average for companies less than 1,000 people, and 9% for 1,000+): women working for companies with 10,000 to 24,999 employees give the lowest rating: 5.98.

Avoid large institutions run by men. The odds are too stacked against your favor, and the system is too big to change.

Survey respondent from Albuquerque, NM

Ratings also varied by sector: women in healthcare consulting gave the highest ratings in terms of their employer supporting their career development, while women working in academia rated their employers the lowest.

Gender equity is good for morale

Perhaps a more predictable indicator of company culture is the percentage of women in leadership positions. For survey respondents who work at companies with less than 10% women executives, the average rating of company culture on a scale of 1-10 (with 1 being the worst) was a striking 5.5. Companies with 50% or more women executives had an average rating of 8.6.

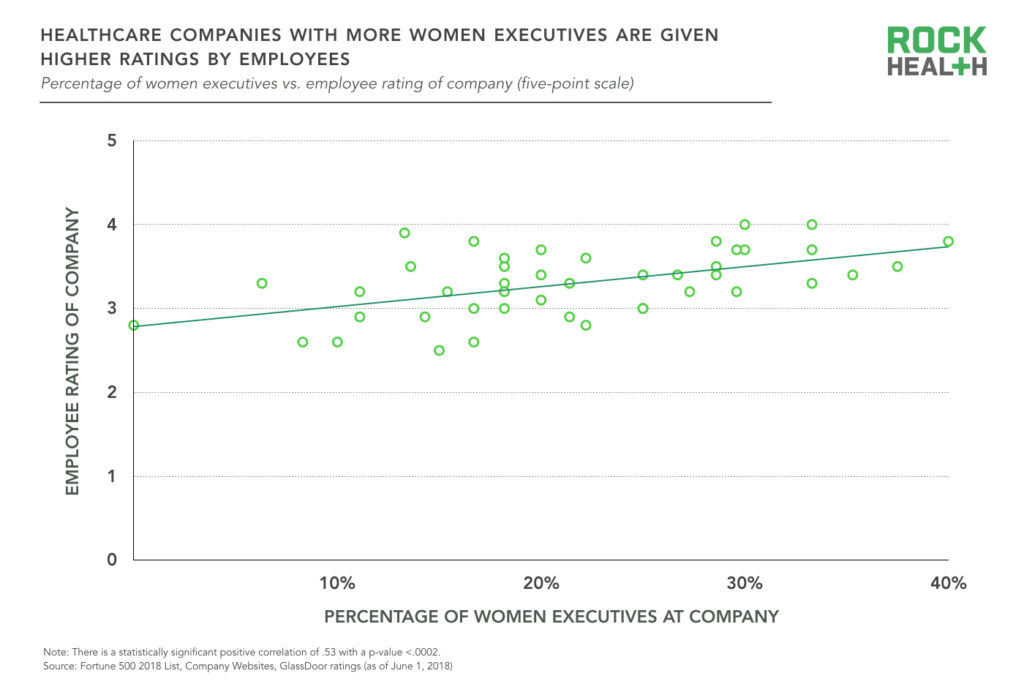

Additionally, we found a positive correlation between company ratings (using data from Glassdoor) and the percentage of women in leadership positions at Fortune 500 healthcare companies2. Companies with higher percentages of women executives are more highly rated by employees.

When employees sense unfairness through gender discrimination and inequality, morale is impacted, which leads to lower productivity and higher employee turnover. Conversely, when employees feel their workplace is fair, they are more happy, loyal, and productive. It’s not about having all-women teams—it’s about having gender balanced teams. One company surveyed 52,000 employees and found that the best performing teams were ones with even numbers of men and women. When the ratio of male and female managers hovers between 40% to 60%, the team is 23% more likely to see an increase in gross profit as compared to teams dominated by one gender.

Compounding inequalities: race matters, too

Source: ThatSister.com

Discrimination often happens at an intersection of different axes; these identities are not mutually exclusive to each other, but instead, have compounding effects. This is referred to as intersectionality.

In 1976, one year after the term “sexual harassment” was defined, five African American women sued General Motors for discrimination in DeGraffenreid v. General Motors. The court determined race and gender were mutually exclusive categories—because the company did not discriminate against African Americans, and they did not discriminate against women, the proceedings found there were no grounds to sue, and the case was dismissed. Years later courts set the precedent to reverse these claims and reached a powerful conclusion: combining different minority identities leads to complex power structures unique to each group. In this case specifically, African American women are subject to discrimination that exists beyond those faced by African Americans or by women.

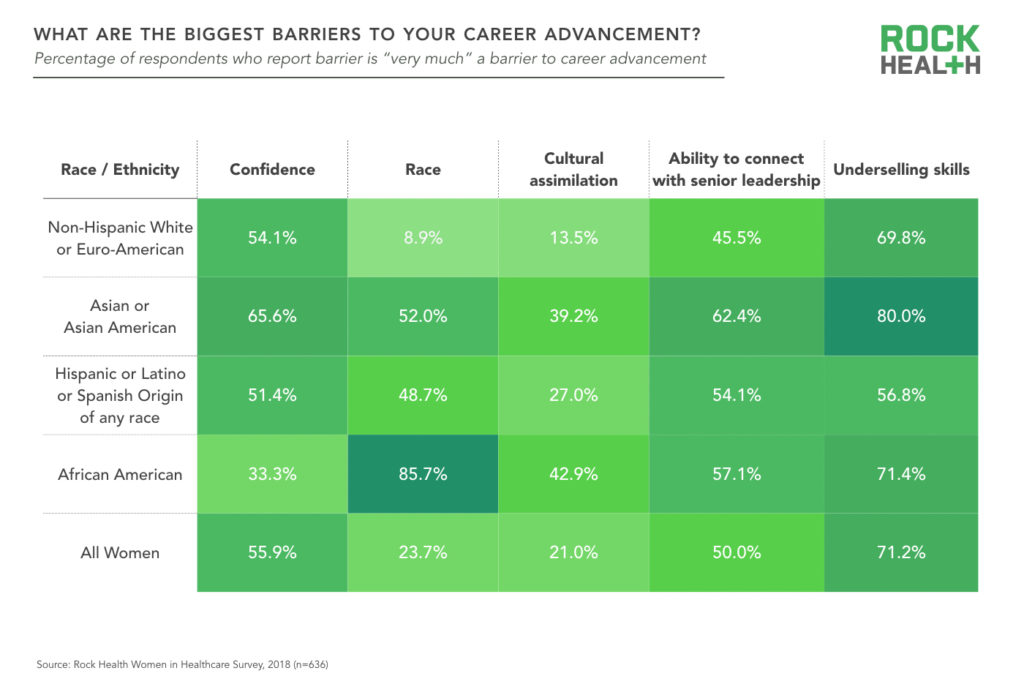

Race and gender collide throughout one’s career, especially for non-white women. Eighty-six percent of African American women surveyed say race is “very much” a barrier to career advancement, compared to just 9% of white women. Still, African American women are also the most confident. Only 33% of African American women surveyed say self-confidence is a barrier, compared to 66% of Asian Americans, 54% of White Americans, and 51% of Latina respondents.

Diversity is not only about gender but race as well. Being an African American woman in a male dominated field is doubly hard and stressful.

Survey respondent from Omaha, NE

Indeed, the challenges vary between races as well. While cultural assimilation and race are seen as significant barriers among Asian American women, this group perceives confidence, underselling of their skills, and ability to connect with senior leadership to be the greatest barriers by wide margins. Harvard Business Review notes this “model minority” is very often forgotten: a blind spot when it comes to workplace inclusiveness. While some diversity reports fail to include Asian Americans as a minority, statistics show Asian Americans (both men and women) are actually the least likely racial group to be promoted to executive levels in the US.

Age is not just a number

Most respondents of all ages identified age as a barrier to career advancement. Women in their 20s reported being judged more harshly for not having decades of experience or graduate degrees. Women aged 30-39 cited “family obligations” and “time constraints” as greater barriers than other groups. Women over the age of 50 stated they face age discrimination, especially in Silicon Valley where hoodie-wearing entrepreneurs born into the iPhone generation are glorified (research corroborates that age discrimination is worse for women).

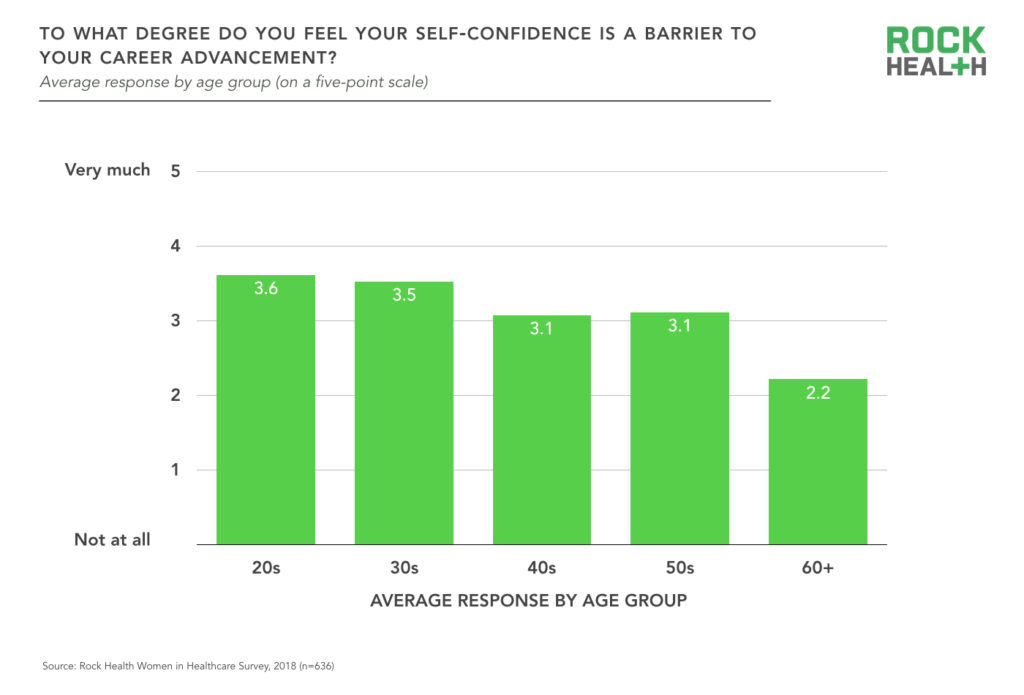

Not surprisingly, self-confidence increases throughout a woman’s career. Women survey respondents in their 20s are most likely to consider self-confidence a barrier, while women over 60 are the least likely. This is confirmed in Zenger/Folkman’s research which shows that as women’s experience increases over time, so does their confidence (men’s confidence increases too, but not at the same clip).

Perhaps the best place to be a woman in healthcare is the Northeast

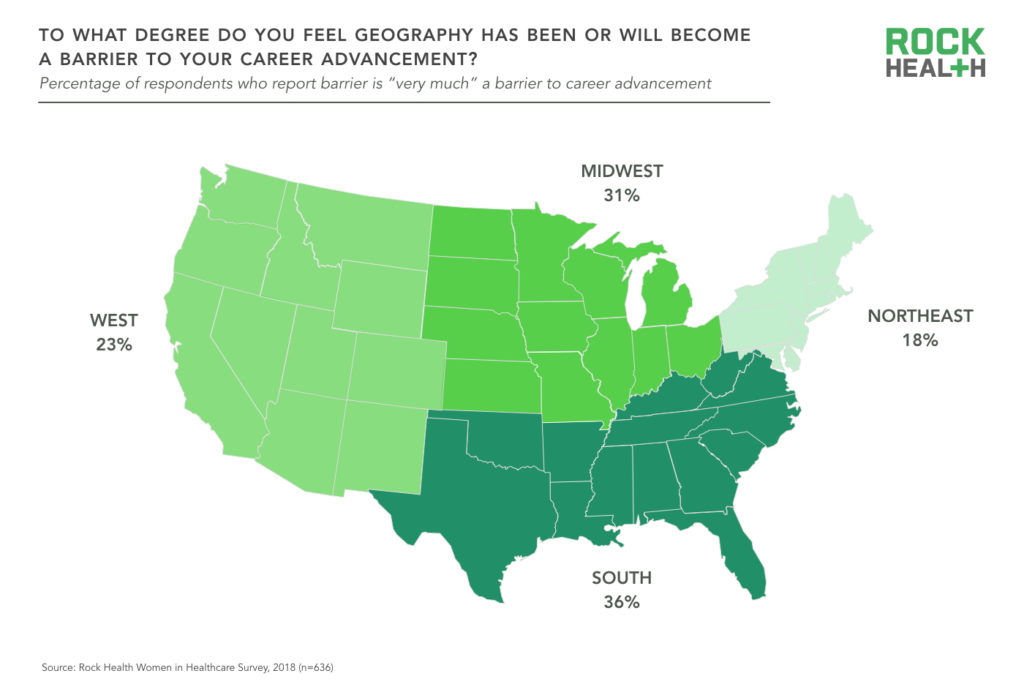

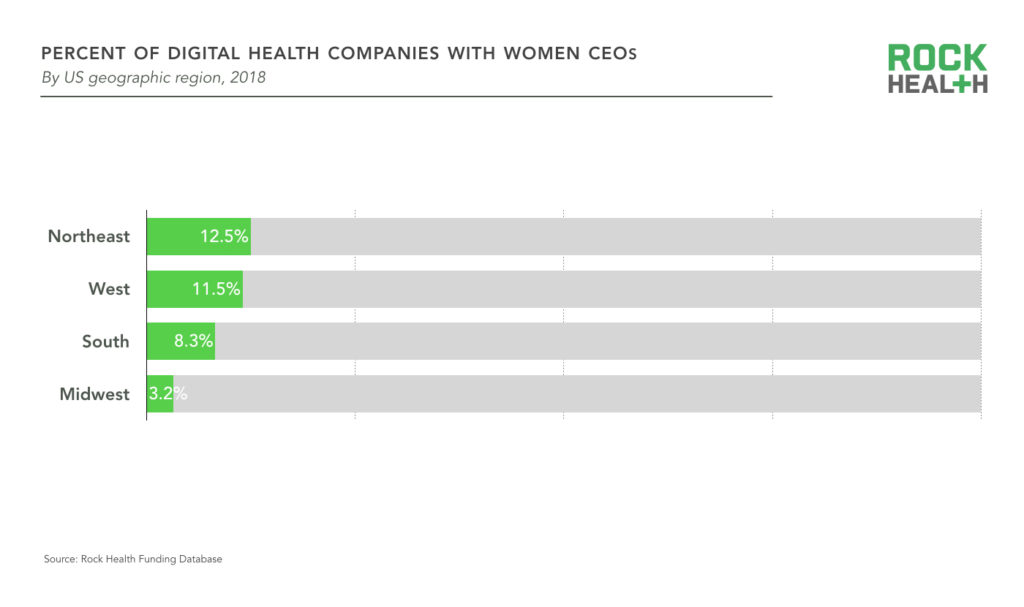

Twelve and a half percent of all funded digital health companies in the Northeast have a woman CEO—higher than any other region (albeit not high enough). And women in the Northeast are least likely to see their location as a barrier to career advancement (18% consider their geography a barrier to career advancement, compared to 27% for the rest of the country). F500 healthcare companies in the Northeast also have a slightly higher average percentage of women board members: 24%, compared to 23% in the West and Midwest, and 18% in the South.

At the other end of the spectrum, roughly a third of women in the Midwest and the South see geography as a barrier to advancement. Further, digital health companies in the Midwest are least likely to have a woman CEO, with just 3% (the South is at 8%). However, the three Fortune 500 companies with the most women executives are all based in the Midwest, one of which (Anthem) has the only woman CEO out of all of the healthcare F500 companies.

Woman-on-woman bullying must stop

In our survey, we heard a lot about the prevalence of women not helping—or worse, intentionally derailing or bullying—other women. One respondent from San Francisco, CA said, “the worst workplace bullying I’ve ever received was from a female board member who oversaw my work.” Another respondent, from Louisville, KY, said, “any poor treatment toward me in my many years within the corporate space has come from other women.” Harvard Business School Professor Robin Ely theorizes that in male-dominated environments—when there appear to be few senior ranking positions available to women—women may begin to view their gender as an impediment and avoid collaborating with or supporting other women.

I’ve had to leave very promising roles at top healthcare tech companies because my female manager/’mentor’ was threatened by me and either purposely or unintentionally blocked my projects and initiatives.

Survey respondent from San Francisco, CA

In a study published in the journal Gender in Management, researchers found “females believed that other women are good managers, but the female workers did not actually want to work for them.” The longer a woman had been in the workforce, the less likely she was to want a woman boss.

I was hoping my current female manager would be more empowering! I hope when I am in her position I will provide better mentorship and increase the visibility of my direct reports.

Survey respondent from Philadelphia, PA

Research from the Workplace Bullying Institute shows that while women only make up 31% of office bullies, they are more likely to target other women (whereas men target both genders at nearly the same rate). Furthermore, when women bully other women, the target of the bullying is likely to lose their job in 89% of the cases (whereas the job loss rate for the bully herself is only 11%). Some call this the Pink Elephant in the room because it’s so pervasive but rarely talked about. One thing is clear: women want it to stop.

Always support other women; the fight is hard enough, don’t put energy into taking other women down.

Survey respondent from Indianapolis, IN

Support groups, mentors, and sponsors are important for career development

To make meaningful change, the mission of gender equality needs to be amplified through communities: to enable connectedness through collective wisdom, spur accountability, and find role models for inspiration and courage.

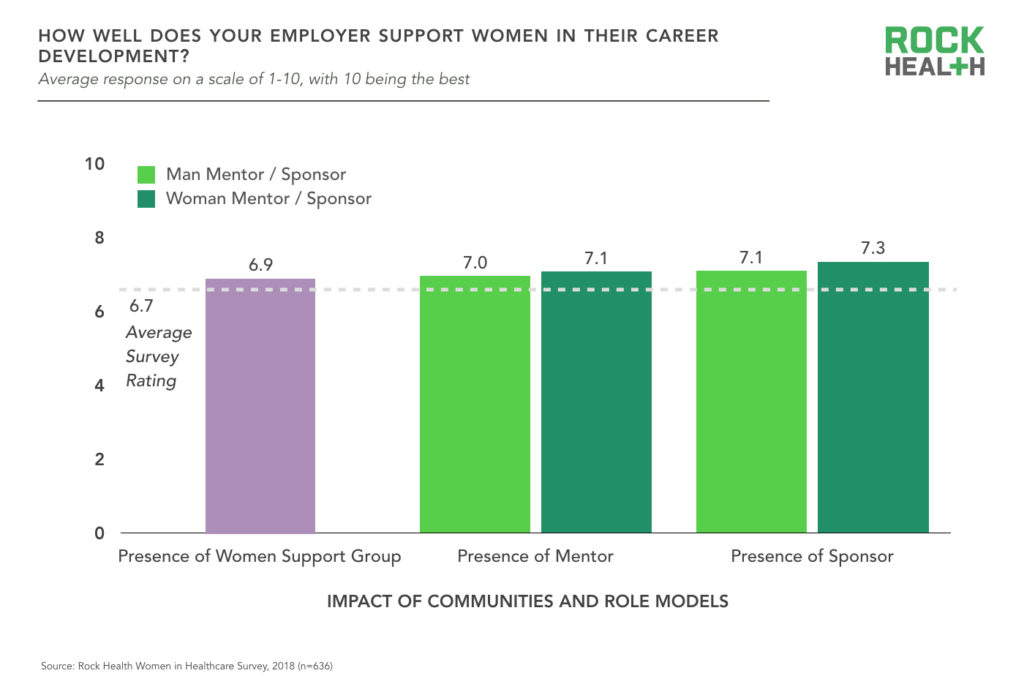

Our survey findings indicate that being part of a women support network or community correlates with a higher overall company culture rating, as does a presence of a mentor or sponsor. However, interestingly, the sponsor’s gender makes a significant difference—having a woman mentor or sponsor positively compounds the effects.

The effects of support groups have numerous other benefits, with more survey respondents in a women’s network (compared to those who are not part of a women’s community) indicating they have just as many role models as their male peers, better ratings for leadership positions for women in their organization, increased confidence, and greater optimism for gender parity in the future.

But employer diversity and inclusion efforts must not be a check-the-box strategy. Efforts must be well thought-out and authentic. They should be developed for and by the stakeholders they intend to impact. And most importantly, they must not only address advancement of women—but ultimately seek to create an absolute even playing field for all employees.

Don’t man up

In a study conducted at Michigan State University, women who described themselves as using traditionally masculine traits (assertive, independent, achievement-oriented) were evaluated as better fits for a job in a male-dominated field than those who emphasized traits often considered feminine (warm, supportive, nurturing). Ann Marie Ryan, a co-author of the study said, “We found that ‘manning up’ seemed to be an effective strategy, because it was seen as necessary for the job.”

But women in our survey warned others against this practice. One respondent from San Diego, said, “Don’t try to be a man, and when you’re not feeling supported—whether by a male supervisor who views you differently, or a female supervisor who finds you threatening—look around for those you identify with who will support you.”

The impact of having a role model, especially one in the workplace, is undeniable: authority can influence the construction of self and identity in a multitude of ways. According to our survey data, the presence of a role model affects not only overall company culture ratings, but also individual attitudes—having a woman mentor or sponsor correlates to less adoption of male behavior traits in the workplace. Not only does this have an inherent message of “you be you,” but it also gives a powerful signal: women can succeed in the workplace without compromising their traits and assimilating into a “dominant” male culture.

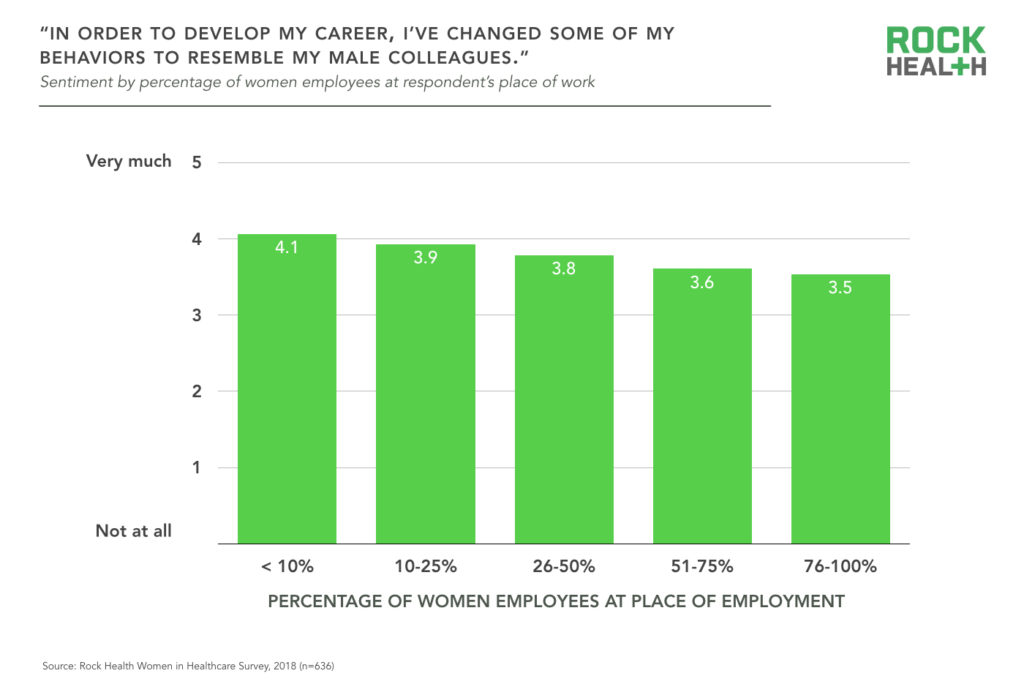

Our survey revealed that the fewer women in a company, the more likely women employees are to adopt behaviors that resemble their male colleagues. We found a strong correlation between the percentage of women employees and exhibiting male traits. This suggests that women changing their behaviors to resemble their male colleagues is not necessarily a constant, but is a function of the environment. Women are more comfortable exhibiting common feminine traits when they are amongst more women.

We need your voice

With awareness comes understanding, and with understanding comes responsibility. Right now, the data tells us this: while there have been marginal improvements for women in healthcare, things aren’t moving nearly fast enough. According to Ernst and Young, the countdown to gender parity is more than 200 years away. If their prediction is accurate, it will take more than eight generations to reach equality (in other words, maybe our great great (…X6) grandkids will live to see it happen).

In writing this report each year, we experience pangs of disappointment when reporting the data on the percentage of women in healthcare leadership positions, and how slowly things move year over year. We struggle to find new angles and novel suggestions from which to craft this report. But we also find so much inspiration and hope in the stories and advice women share with us. It’s telling that 2018 is the year we received more survey responses than ever before. This year we’ve seen more awareness and motivation to create workplaces that support and advance all employees. The language (via words and hashtags) has crystallized, and the conversation is happening aloud.

With enough women and men on board to fight for gender equality, we can find courage in each other—and collectively spur a greater change. As Mary Anne Radmacher wrote, “Courage does not always roar. Sometimes courage is the quiet voice at the end of the day saying, ‘I will try again tomorrow.’” And so we will.

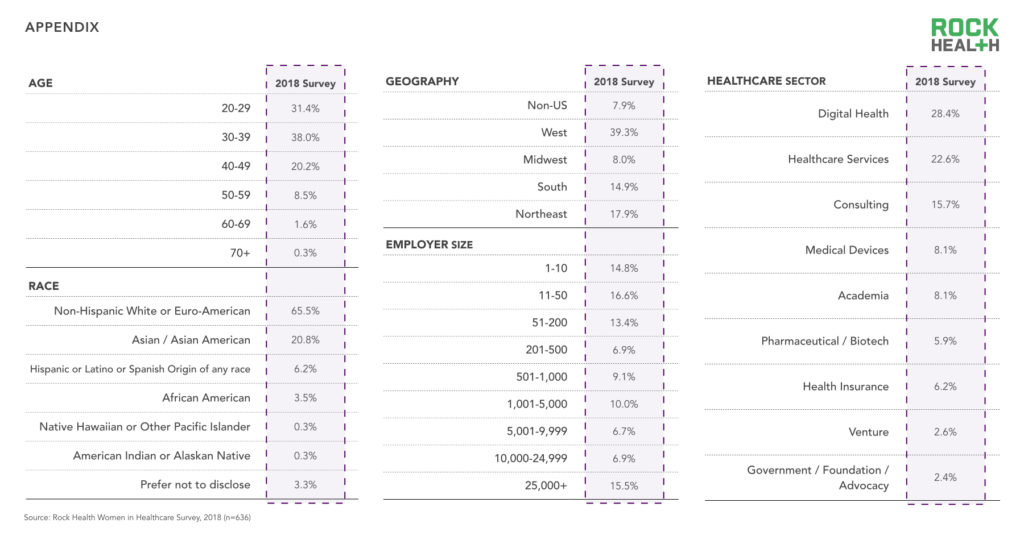

1Methodology and survey sample

Rock Health conceived and wrote all the questions and materials used in the 2018 Women in Healthcare survey. The survey was marketed through social media and direct emails. The target audience was women working in the healthcare industry in the US. The survey began on May 14, 2018 and ended on June 15, 2018. The sample size is n=636. Findings from the data were based on internal analyses conducted in Excel and R. Only responses from people who disclosed their identity as a woman were included in the analysis.

2Our data showed a statistically significant correlation between the percentage of women in leadership roles and overall employee company ratings. Given the sample size of organizations (46) and method we used, more research is needed to explore this association.