The state of gender equity at healthcare startups and VCs in 2019

Over the course of the last year, we’ve witnessed notable advances in gender equity within business and society at large. The US Women’s National Soccer Team came home with the World Cup and brought the gender wage gap to the national stage. A record number of 127 women hold seats in Congress. Both The Lancet and NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins have committed to “no manels” at events they host. And in our own backyard, a couple efforts caught our attention—Jordan Sale launched 81 cents, a startup to help address the gender pay gap by crowdsourcing information for compensation negotiations, and Salesforce spent $8.7M equalizing pay for its employees.

Yet progress continues to come slowly, and the data on gender equity offers a sobering look at just how far we still have to go to reach a world in which women and men are equally represented, treated, and compensated in business. The World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Gender Gap Report estimates it will take an astonishing 208 years to reach gender equality in the US. Women founders own $0.48 of equity for every dollar men own, and just 22.5% of Fortune 500 board members are women.

As an early-stage investor, Rock Health itself plays a role in bringing new entrepreneurs into the digital health sector and supporting newly-formed companies. From this vantage point, we encounter first-hand the significant gender disparities among industry healthcare leaders, investors, and entrepreneurs—as well as the challenges organizations face in cultivating gender equity. That’s why every year we report on the state of gender diversity in healthcare—it’s an opportunity to take stock of the progress being made and to provide actionable recommendations for the road ahead. A few key perspectives guided the report this year:

- Our Motivation: Diversity is a powerful competitive advantage for business. Diverse teams realize superior financial performance and are better able to innovate and attract and retain the best talent. In the startup space specifically, companies with women on their founding teams are likely to exit one year faster compared to the rest of the market. Despite this, the “business case” isn’t our driving force for this report. In light of the disparities that exist in workplaces and beyond, we’d suggest that belief in the business case is secondary to a belief that working towards more equitable workplaces is simply the right thing to do. Our intention is to drive measurable change for the current and future talent in our industry.

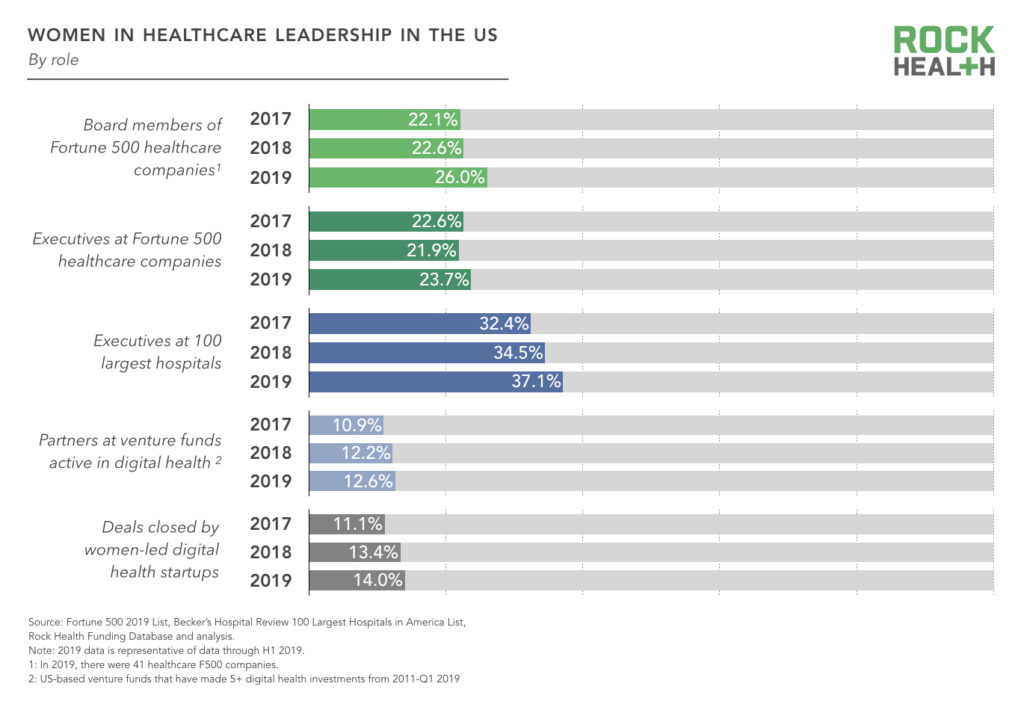

- Our Focus: In this report, we examine gender representation among key healthcare leadership roles at Fortune 500 companies, venture capital firms (VCs), and startups. Gender representation in leadership is, however, just one measure of one type of diversity. Though we anticipate many of the tactics highlighted in this report will promote equity and inclusion for people of all identities, the intent of this report is to shine a spotlight on the significant overrepresentation of men in healthcare leadership, particularly within VCs and at startups, and to uncover tactics to address this disparity.

- Our Aspirations: We are humbled by the scale of this problem, and when we examine our own practices, we are not overachievers. We are tackling these issues on a daily basis, too. This work can be personal, controversial, and require us to sit outside of our comfort zone. In this report, we seek to contribute within areas most proximate to our work in the healthcare VC and startup ecosystem. We know the problem is much bigger than we’re able to cover here. We aspire to contribute to the discussion where we have the most expertise and to collaborate with others on the broader issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion across all underrepresented groups. We also hope to offer a safe space for learning and growth through the respectful exchange of ideas. Please reach out anytime if you’d like to connect with our team at research@rockhealth.com.

This year we conducted a survey in July 2019 of 218 men, women, and non-binary respondents working at healthcare startups and VCs to understand their attitudes toward gender equity, and how they perceive initiatives at their organizations to promote the advancement of women.1 We also spoke with 15 leaders in healthcare including startup CEOs, VC partners, and leaders focused on improving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within this sector. Three themes emerged:

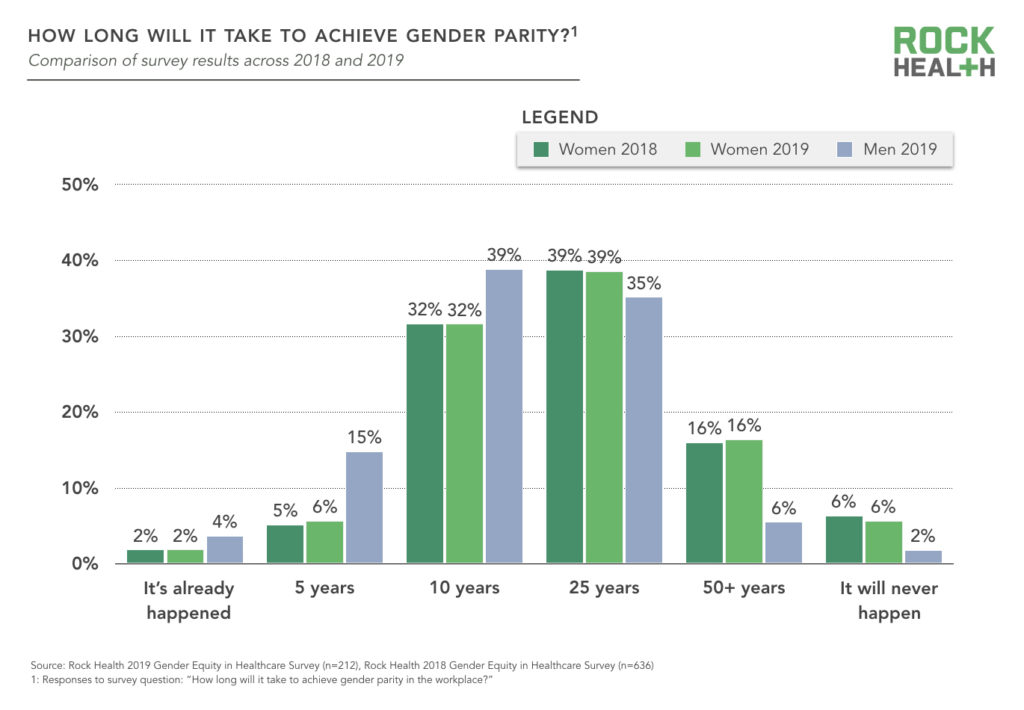

- We are far from gender parity—but people have high expectations for progress. Despite significant disparities today, industry leaders and employees share a belief that gender parity can be achieved within our lifetime.

- The most common initiatives to promote gender equity may not be the most effective. We asked employees at healthcare startups and VCs which initiatives they saw in place to promote gender equity, and which were the most effective. Most companies have some initiatives in place; however, gaps exist. The most commonly-implemented initiatives are not aligned with what respondents report are the most effective. This signals an opportunity for organizations to reassess and align their culture and diversity initiatives with what employees find most impactful.

- There’s a (perceived) commitment gap between individuals and organizations. Individuals self-report higher levels of commitment to gender equity than the leadership commitment they perceive at their own organizations. Section Three explores why organizations are perceived to be less committed than the people who comprise those organizations.

It’s clear that individuals—specifically those completing our survey—are ready for change, and personally committed to making it happen. To support organizations as they move to match this energy and create diverse, equitable workplaces, the final section of this report offers an overview of the tactical solutions leaders can actively use to advance gender equity.

I. We are far from gender parity—but people have high expectations for progress

(Still) Moving at a Snail’s Pace

Women continue to occupy just a fraction of leadership roles in healthcare despite making up 65% of the healthcare workforce—this holds true across all healthcare leadership roles. Among Fortune 500 (F500) healthcare executive teams and boards, US hospitals, healthcare VCs2, and digital health startups, gender equity is improving—but just as we reported last year, improvement has been slow. F500 healthcare company boards made the most progress by increasing women representation from 22.6% in 2018 to 26.0% in 2019. US hospitals continue to have more women representation than F500 healthcare boards and executive teams do, at 37.1% in 2019. VCs and startups made the least progress—the percentage of women partners at VCs grew by 0.4 points and the percentage of deals closed by women CEOs of digital health startups increased by just 0.6 points.

Given the slow pace of change, it is worth asking how long it might take to reach gender parity in each respective industry leadership role. Taking inspiration from The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, we constructed three models to simulate the number of years it will take to achieve gender parity for: partners at healthcare VCs, F500 healthcare executives, and F500 healthcare board members. We relied on several publicly-available sources for baseline gender ratios and average tenure3 across different segments of industry. With these in hand, we project how long it will take each of these segments to reach gender parity. The main variable is the rate at which women are hired into these roles—we built multiple scenarios within each model to test what happens if women are hired into open leadership positions at rates of 50%, 75%, and 100%.4

If, starting now, 50% of all newly-hired healthcare VC partners are women, it will take 94 years to reach 45% women partners and 132 years to reach 48% (due to the asymptotic nature of the curve, it will take longer to make incremental progress as women representation approaches the 50% threshold).5 The outlook for F500 healthcare executive teams and boards is similar—executive teams will wait 77 years to reach 45% women in leadership, while boards will wait 72 years.

Parity comes more quickly if women are hired at a higher rate than 50%. The VC model shows if healthcare VCs were to hire only women as partners starting today, the mix of partners would reach 45% women in 23 years. At a hiring ratio of 75% women, gender parity among VC partners occurs in 35 years. By contrast, if one woman and three men are hired for every four investor vacancies, these roles are destined to reach 25% women representation—and stay there forever.

Despite the harsh math for leadership roles across the healthcare industry, the digital health sector in particular is (slightly) closer to achieving a balanced gender ratio than other industries. Healthcare VCs, for example, employ 13% women partners compared to the overall VC average of just 10%.6 While 14% of US digital health deals provided funding for women CEOs so far this year,7 women CEOs represented a mere 11%8 of all venture deals across all industries.

Individuals optimistic about the ability to change

Among our survey of healthcare startup and VC employees, nearly 80% of women respondents believe they will see gender parity in the workplace within 25 years. Men respondents seem to be slightly more optimistic than women: 54% of men respondents believe gender parity will be reached within ten years, compared to 38% of women respondents.

Women may be anticipating the array of barriers standing in the way of leadership roles —and factoring them into their own ambitions

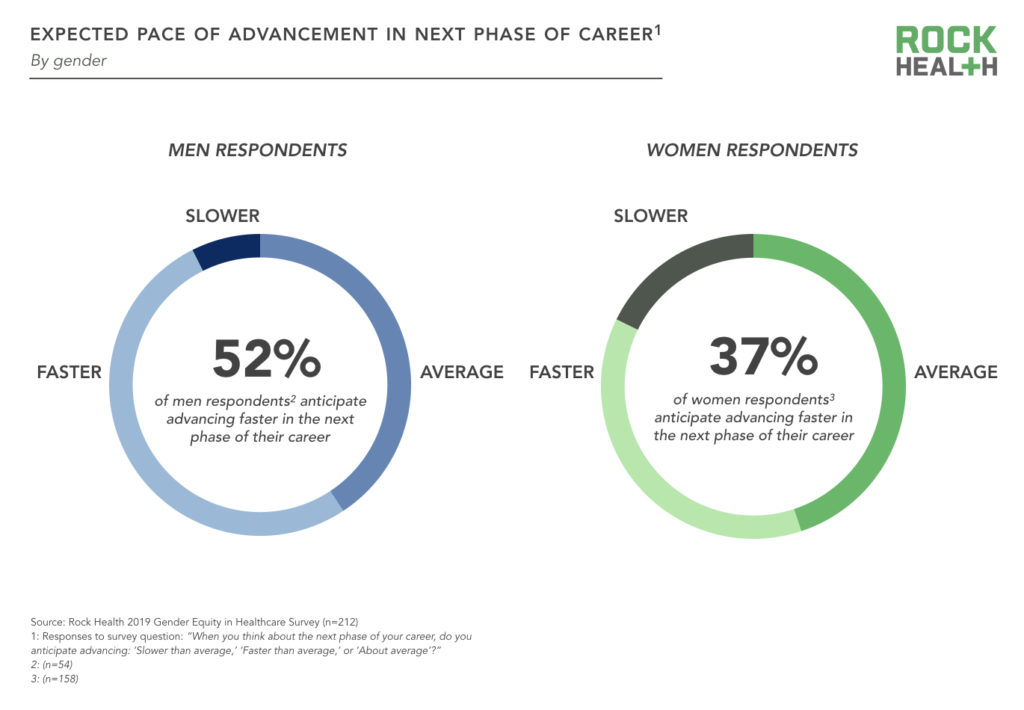

Our survey respondents indicate women may have different career expectations than men do. For instance, more men respondents than women respondents report that they anticipate advancing faster in the next phase of their career.

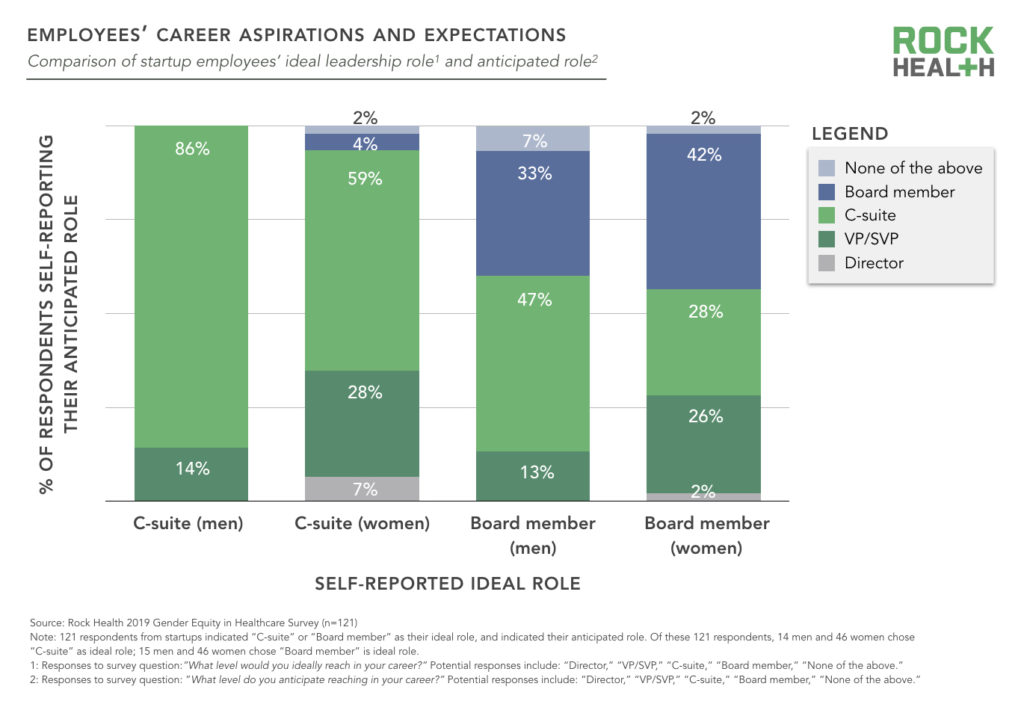

And women report a larger gap between their career ambitions and self-perceived likelihood of reaching those ambitions. Seventy-one percent of women respondents who work at a healthcare startup report having a career goal of reaching the C-suite or becoming a board member. However, of the 36% of women desiring to reach the C-suite, only 59% expect they will achieve this, compared to 86% of men with the same goal.

One might look at this data and assume women are simply less confident in their abilities than men. But professors from Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business and Harvard Business School have debunked the myth of women having inherently different traits than men, despite the pervasiveness of these stereotypes (e.g., women are worse negotiators, women lack confidence). They concluded that inequality in the workplace is often fueled by company culture and norms that treat men and women differently.

We believe real change is seeded through structural shifts undertaken by healthcare startups and VC firms themselves instead of encouraging individual women to conform to an existing paradigm. We crafted our survey around the ways these organizations can build work environments that support the advancement of women—and overcome the challenges that remain.

II. The most common initiatives to promote gender equity may not be the most effective

In this year’s survey, we asked employees of healthcare startups and VC firms which initiatives, if any, their workplaces have implemented to support women’s advancement (e.g., flexible work arrangements, women’s communities and employee resource groups (ERGs), and unconscious bias training). If a respondent’s workplace had these initiatives in place, we then asked them how effective the initiatives are in supporting the advancement of women.

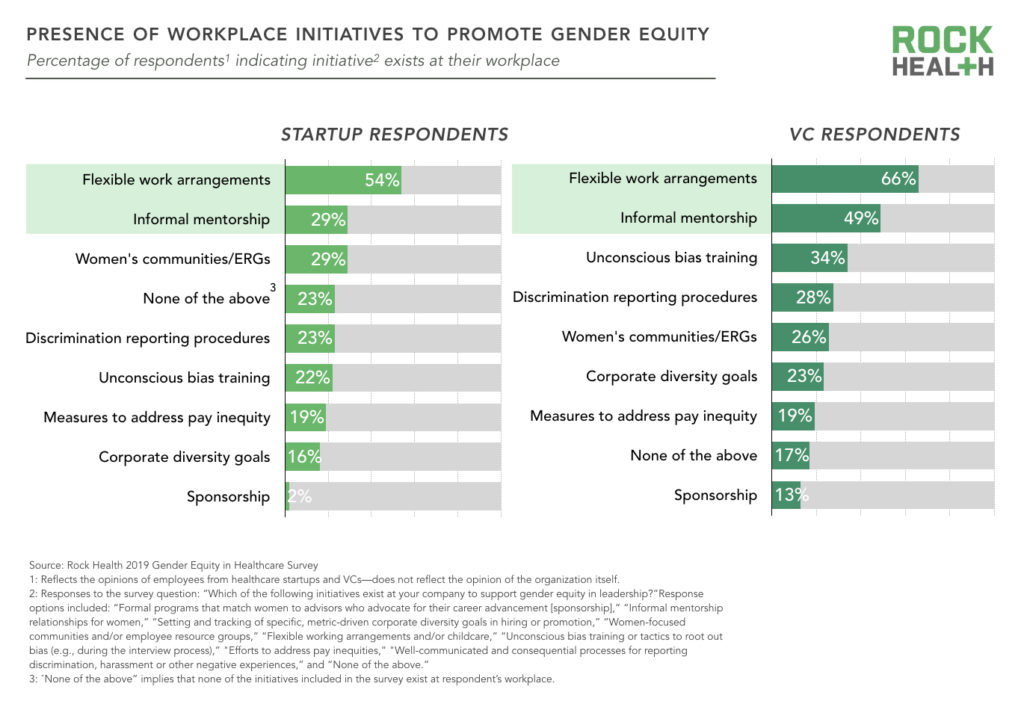

According to their employees, most of the startups and VCs represented in our survey are unlikely to have initiatives in place to support gender equity. The exception is flexible work arrangements (e.g., the opportunity to work remotely, and during off-hours)—employees report that the majority of startups and VC firms offer this flexibility. At startups, informal mentorship and women’s communities were the next most common initiatives, but still only 29% of startup employees report these opportunities are available at their workplace. Strikingly, 23% of startup employees and 17% of VC employees report that none of the initiatives we asked about are offered at their workplace. These initiatives do not represent every possible means to support women in leadership—they are a subset of tactics. But they do represent a path forward for firms that are considering how they might formally operationalize a strategy to support a more diverse workforce and, ultimately, leadership ranks.

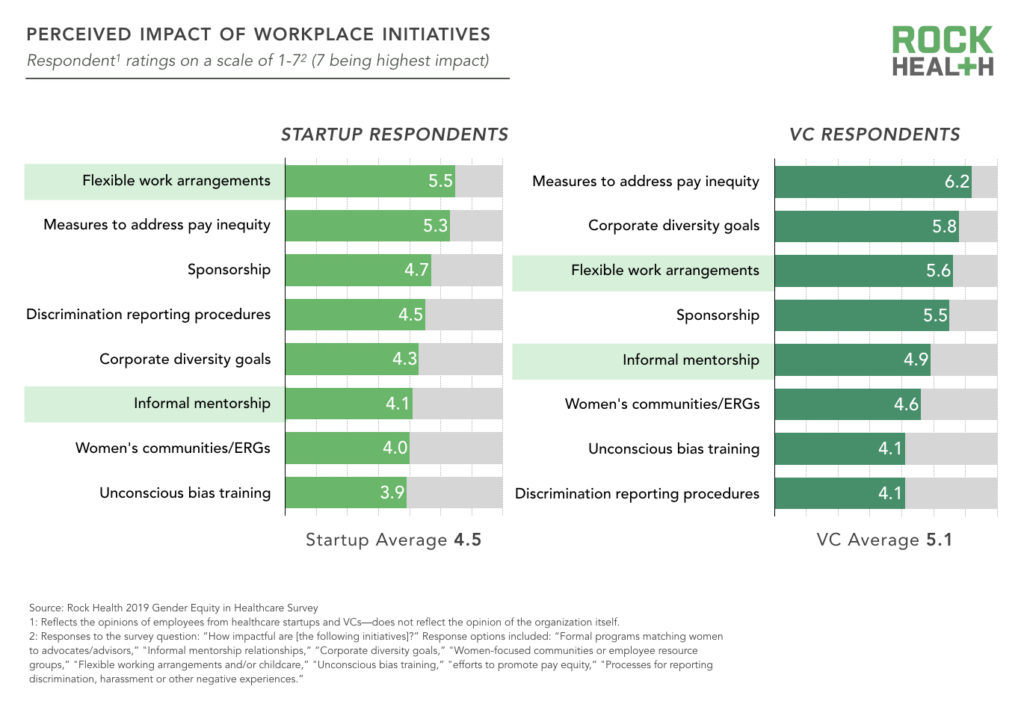

We believe the action of implementing initiatives that support gender equity is important—but what’s even more important is the initiatives’ impact. Survey respondents highly value certain initiatives—for instance, on a scale of 1-7, VC respondents rated the effectiveness of “measures to address pay inequity” as 6.2. But on the whole, we found inconsistencies between the initiatives most likely to be in place versus those deemed to be the most effective. For instance, some of the most common initiatives implemented in the workplace— informal mentorship and women’s communities—did not rank consistently as the highest impact initiatives. Additionally, two of the highest impact initiatives—addressing pay inequity and sponsorship—were rarely implemented among startups and VC firms. These gaps can serve as a starting point for leaders and employees to discuss the effectiveness of current initiatives, and what might be missing to make a difference in employee engagement and advancement.

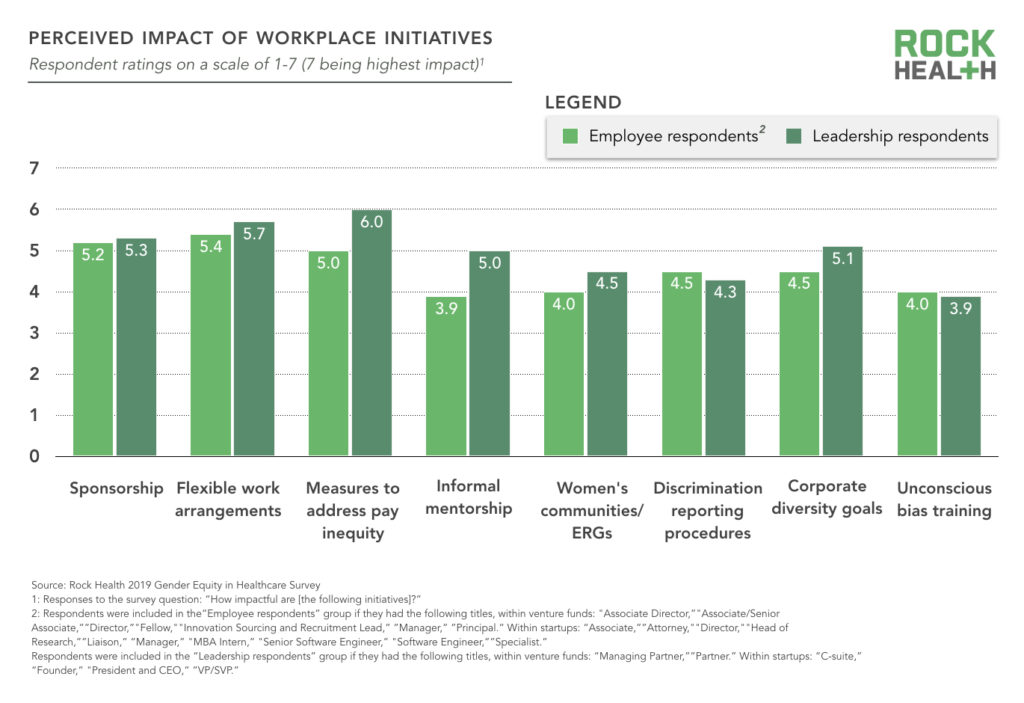

This data unearths another important insight: leaders tend to think these initiatives are more impactful than they actually are. On the whole, respondents in leadership roles9 rated the impact of these initiatives more highly (average of 5.0) compared to employee respondents10 (average of 4.6). The biggest delta exists between leaders and employees when it comes to rating the impact of informal mentorship—leaders may assume more junior employees are benefitting from these relationships more than they actually are. Of note, both employees and leaders ranked sponsorship as more effective than informal mentorship, despite informal mentorship being one of the most commonly implemented initiatives.

III. There’s a (perceived) commitment gap between individuals and organizations

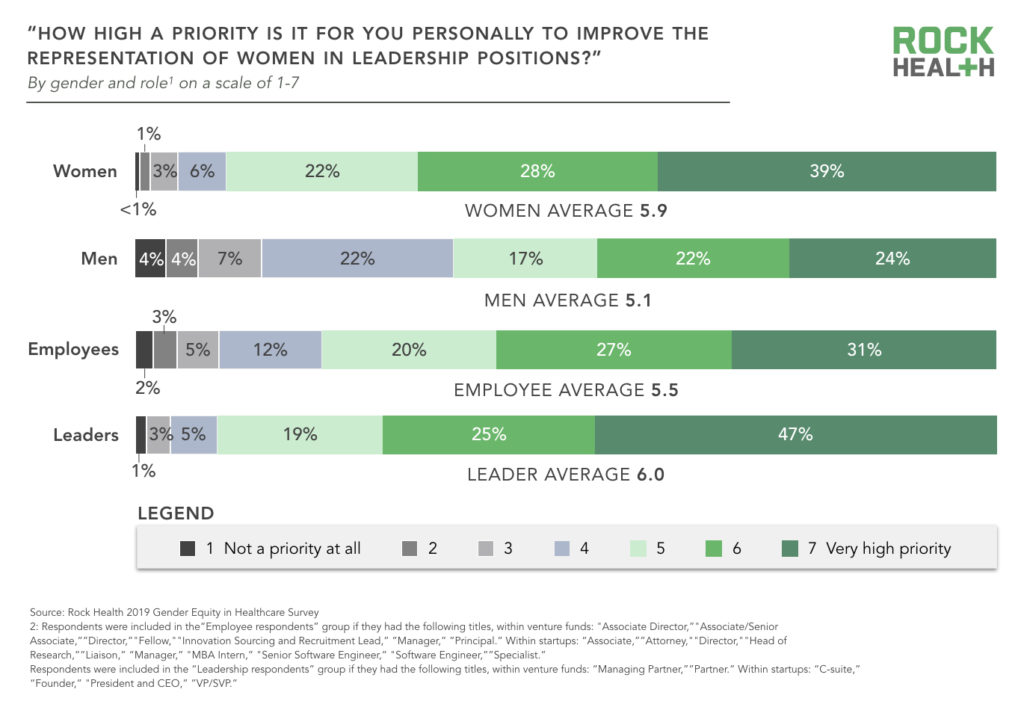

The vast majority of respondents feel personally invested in improving the representation of women in the workplace. This is true across all groups—the majority of women, men, employees, and leader respondents across startups and VCs reported feeling accountable for driving change. Women and leaders feel this accountability particularly acutely.

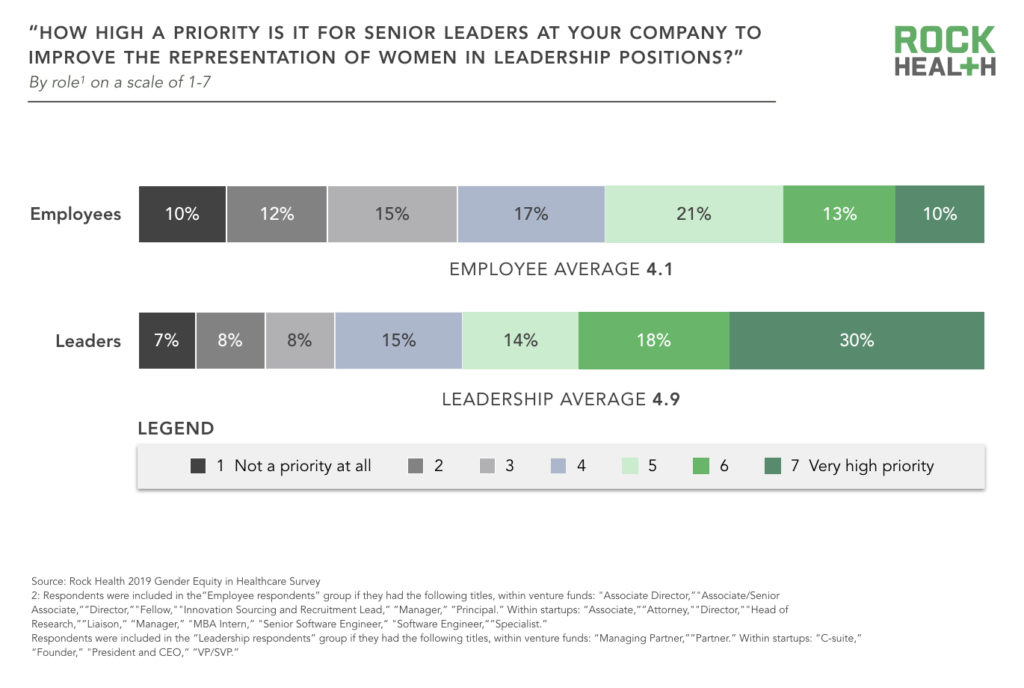

However, respondents report not seeing the same level of commitment at an organizational level. Among employee respondents, nearly 40% feel their senior leaders are not particularly committed to improving gender diversity in leadership roles. This perceived gap between one’s individual commitment and their organization’s commitment can be particularly taxing, especially among the affected populations who often must shoulder both the challenge of being in an underrepresented group as well as the burden of advocating for their own and others’ advancement.

This gap between perceived individual and organizational commitment starts to close when there is greater gender diversity on executive teams. Perhaps not surprisingly, employees at firms with 50% or more women in leadership roles report greater confidence in their company’s commitment to gender equity than leadership teams comprised mostly of men.

Every person we interviewed agreed leadership commitment is key to turning the tides on representation. But commitment isn’t enough—leaders must implement strategies that promote gender equity.

Tactical tips from investor and startup leaders

In addition to the initiatives outlined above, conversations with founders, investors, and DEI advocates revealed additional strategies for building a workplace supportive of gender equity. Here’s what we heard:

- Start early. Though startups face competing priorities and limited resources, it’s important to prioritize creating a culture of diversity and inclusivity from the outset. “Unless you make gender diversity a priority from the very beginning, and establish it as a core value or priority, it’s very difficult to fix later on. Shifting from a company that’s 90% white male to one that is 50-50 even after a year of operations is going to be a major challenge with serious implications. You hamstring the business and most importantly the future potential success of the business by not making it a priority from the very beginning.” – Elli Kaplan, Founder and CEO, Neurotrack

- Recognize that without committing—through initiatives, explicit diversity goals, or other accountability measures—companies are likely to perpetuate the status quo. A majority of employees from healthcare startups and VCs reported they do not have a stated diversity goal for leadership roles. Explicit goals aren’t the only route to gender parity. But without stated attention and accountability, DEI efforts can fall to the wayside compared to other pressing business priorities. “I don’t think this culture exists because people wake up every day and want to support the patriarchy. [A lack of diversity] is just something that reflects what’s happening in our wider society. If you don’t actively counter that culture, you’ll wake up one day and see that your team lacks diversity not because you’re a bad person but because you didn’t fight the tailwinds of the prevailing culture.” – Toyin Ajayi, Co-Founder and Chief Health Officer, Cityblock Health

- Take the pulse of the organization to find opportunities. Cityblock and Omada leadership use a third-party employee feedback and analytics platform to create feedback surveys with DEI-specific questions in an effort to understand how their employees (and specific groups of employees) feel about company culture and what improvements they could make. OODA Health hired a gender consultant who interviewed employees to understand the perspectives, gender biases, and blind spots that might be holding certain groups of employees back from reaching their potential. The consultant worked with leadership to ensure they are equipped to be champions of diversity.

- Transparent expectations and salary ranges can help weed out bias. Startup founders offered tactics to make headway on closing the gender pay gap: (1) Stick to explicit salary bands—this can help prevent unconscious gender bias from finding its way into negotiation discussions. (2) Clearly communicate role expectations and what is required to reach the next level. “Every comp cycle, we make sure we’re upholding the equal pay pledge by analyzing any potential comp disparity across gender lines. This is low-hanging fruit. Spend the 20 minutes in Excel to do this! It’s not hard. It’s also important to do everything you can to avoid off-cycle promotions and compensation changes, because these are two areas where bias can creep in and introduce pay inequity.” – Sean Duffy, Co-Founder and CEO, Omada Health

- At venture funds, bringing transparency to the deal flow pipeline can unearth unconscious bias. The Rock Health venture team tracks the gender of co-founders and founders in our deal flow pipeline. This year, 18% of the companies we reviewed had a woman CEO and 33% had a woman on the founding team. Four of the seven companies we’ve invested in this year (Natalist, Arine, and two currently undisclosed) are led by women CEOs. Tracking this data enables us to more deeply analyze where gaps in our pipeline may exist—whether it’s how we source deals or who we ultimately decide to fund. We also have begun tracking why we pass on companies, with the intention of uncovering any unconscious biases in our decision-making that may disproportionately impact women-led companies. Conversations with other funds revealed such tracking is fairly rare, though some like Kapor Capital offer leading examples to follow. “When I go and speak about the importance of gender and racial equity, there is a belief that there is a trade-off between equitable practices and venture scale returns. We published a social impact report that details the demographics of not only our internal team but also our portfolio companies. We’re in the top quartile in growth and we have a diverse team. We’ve actually gotten more deals after switching to a diversity focus because people want to have investors that understand their background. As entrepreneurs demand it more of their investors, just as tech companies had to start publishing numbers, there will be more such info publicly.” – Ulili Onovakpuri, Partner, Kapor Capital

- As the expectation for diversity increases, the risk of tokenism rises. Multiple interviewees noted that while they have seen more women be promoted or hired into partner roles at funds, they are worried those women may not have the same degree of responsibility on the investment committee, or may be the first to be let go in the event of a downturn. Rather than hiring or promoting along the lines of gender, organizations can diversify their pool of candidates and minimize unconscious bias, going beyond one’s current network and ensuring the organization is truly finding the best candidate for the job. “I don’t like being the ‘female’ founder, I like being the founder who is smart and skilled. I’m not interested in being the token female.” – Kelsey Mellard, Co-Founder and CEO, Sitka

- Allies are critical. It can be daunting for men and others to step up as allies—advocate for underrepresented groups, make space for less heard voices, and call out unconscious bias—if they don’t feel they have a safe space to make mistakes. Helping those with privilege step into ally roles is critical to supporting underrepresented groups. “Sometimes it’s hard for people to speak for themselves, if you’re there and you see it you can speak up for them. There’s a lot less risk for someone who’s an ally versus the person themselves; allies are not directly affected by the fallout.”- Ellen Pao, Founder and CEO, Project Include

- Use the resources that are available! Project Include’s program, Startup Include, provides early-stage startups and CEOs a goal-oriented, eight-month program designed to foster peer conversations, understand employee satisfaction, and provide guidelines and frameworks to start working on inclusion. They also have a wealth of (free) diversity and inclusion resources and tools.

There are many more tactics organizations are using to support women’s advancement into healthcare leadership roles. We’d love to hear what’s working at your organization, and what’s working for you personally. Email us at research@rockhealth.com and find us on social media @Rock_Health.

Special thanks to:

Sean Duffy (Omada Health), Kelsey Mellard (Sitka), Elli Kaplan (Neurotrack), Leah Sparks (Wildflower Health), Toyin Ajayi (Cityblock), Seth Cohen (OODA Health), Ulili Onovakpuri (Kapor Capital), Michael Greeley (Flare Capital), Annie Lamont (Oak HC/FT), Jenny Abramson (Rethink Impact), Aly Lovett (Radian Capital), Ellen Pao (Project Include), Cadran Cowansage (Elpha), Rachel Talanian (MassChallenge), Natalie Cantave (MassChallenge), and Nina Kandilian (MassChallenge).

Footnotes

1Methodology

Rock Health collected 218 survey responses from people of all genders based in the US. Rock Health partnered with Oliver Wyman to develop a portion of the survey questions. 158 survey repsondents self-identified as women, 54 self-identifed as men, and six self-identified as gender-fluid, transgender, non-binary, or preferred not to disclose a gender identification. 171 respondents (129 women, 39 men, 2 non-binary individuals, 1 prefer not to disclose) reported working at a healthcare startup and 47 (29 women, 15 men, 1 gender-fluid individual, 2 prefer not to disclose) reported working at a healthcare venture fund. The data is intended to offer directional guidance to explore issues more deeply. The survey is not a representative sample of the healthcare startup or VC employee population.

To supplement the survey findings, we conducted 15 interviews with leaders in healthcare including startup CEOs, VC partners, and leaders focused on improving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within this sector.

2Analysis includes 240 US-based venture funds that have made at least five digital health investments between 2011-Q1 2019.

3Average age for VC partner is conservatively set as 37.5, with an average tenure of 28.5 years, and retirement at 66. Brian DeChesare, Venture Capital Careers: The Complete Guide; Average C-level executive tenure is 5.3 years, set as six in model for conservatism. Korn Ferry Institute, Age and Tenure in the C-suite: Korn Ferry Institute Study Reveals Trends by Title and Industry, 2017; Median board tenure set at 8.7 years. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, Board Refreshment Trends at S&P 1500 Firms, 2017. Another key assumption in the model is the assumed growth rates in the number of roles available (based on natural inflation trend and rate of retirement).

4We recognize that a 100% women hiring rate is an unrealistic case—we offer it to illustrate how long the shift to gender parity would take under an extreme assumption that will not occur.

5The model assumption of a hiring ratio of 50% women (and 50% men) results in a curve that is asymptotic at 50% (and will therefore never quite reach the 50% parity mark).

6International Finance Corporation, Oliver Wyman, RockCreek, Moving Toward Gender Balance in Private Equity and Venture Capital, 2019.

7As of Q3 2019, Rock Health Venture Funding Database.

8Pitchbook and All Raise, All In: Women in the VC Ecosystem, 2019.

9Respondents from VC firms who self-identified as “Managing Partner” and “Partner” were categorized as leaders. Respondents from startups who self-identified as “C-Suite,” “Founder,” “President and CEO,” and “VP/SVP” were categorized as leaders.

10Respondents from VC firms who self-identified as “Associate Director,” “Associate/Senior Associate,” “Director,” “Fellow,” “Innovation Sourcing and Recruitment Lead,” “Manager,” and “Principal” were categorized as employees. Respondents from startups who self-identified as “Associate,” “Attorney,” “Director,” “Head of Research,” “Liaison,” “Manager,” “MBA Intern,” “Senior Software Engineer,” “Software Engineer,” and “Specialist” were categorized as employees.