An apple a day, but keep the doctor in play: A primer on food as medicine trends, solutions, and business models

Food as medicine, food is medicine, “let food be thy medicine”—the concept of applying evidence-based nutritional science to care delivery is as old as modern medicine. Yet, recent trends across healthcare, technology, consumer experience, and food culture are seeding a new life for this philosophy with old roots. Between 2023 and Q1 2024, $373M has been invested across 22 digital health startups developing food as medicine (FaM) offerings.1 And large companies within and outside of healthcare—retailers, payers, providers, and tech—are partnering and building solutions to seize the opportunity. New models are sprouting from today’s FaM innovators, who are building solutions that are tech-enabled, outcomes-based, and integrated into primary and chronic care.

There’s no shortage of new buzzwords and descriptors to describe FaM—food “farmacies”, produce prescriptions, nutrition as a service (NaaS), foodcare (a newer term to describe the broader market2). So what’s fresh and what’s stale? This article provides a primer on the dynamics accelerating the FaM market, how players are partnering to advance the ecosystem, service components in the FaM value chain, and—of course—who’s paying. Our aim is to equip leaders across the ecosystem with a foundational understanding of the market to drive creation of thoughtful and innovative strategies to support consumer nutrition.

Fertile grounds for new FaM models

The opportunity for well-designed FaM programs has never been greater. While many healthcare players are active in the space, evolving payer and consumer priorities around tech-enabled nutrition support are particularly strong drivers of current market momentum.

Consumers want to eat healthier, but need guidance

Shifting consumer behaviors and needs related to food culture, diet, and wellness are breathing new life into the FaM space. Nearly 60% of Americans say the pandemic changed the way they eat, with 20% saying they made major health-conscious changes (e.g., eating more fresh produce, reducing consumption of sugar, fats, salt, and red meat). Despite increasing focus on diet as a health priority, nearly 50% of consumers find it hard to understand what foods are best for their health and 68% receive conflicting information about what foods they should eat or avoid. Unsurprisingly, more than one-third of consumers plan to increase their spend on nutrition apps and services in the next year.

Payers want to control rising costs of diet-related disease

Payers continue to grapple with the rising costs of treating the nearly 50% of Americans with diet-related disease—$1.1T per year, the same as total consumer grocery spend. For many of these individuals, social determinants of health (SDOH) play a key role. In 2022, 12.8% of U.S. households (44M individuals) were food insecure, the highest rate since 2014 and the largest single-year increase (+33%) since 2008. While government assistance programs like SNAP and WIC have expanded to address the need, the cost of food remains one of the highest economic concerns for Americans. FaM programs offer payers an avenue to help consumers change their relationship with food before requiring medication, create step-down paths from costly medications like GLP-1s, and improve quality of life and outcomes while on medication.

New life emerges: Market responses to the opportunity

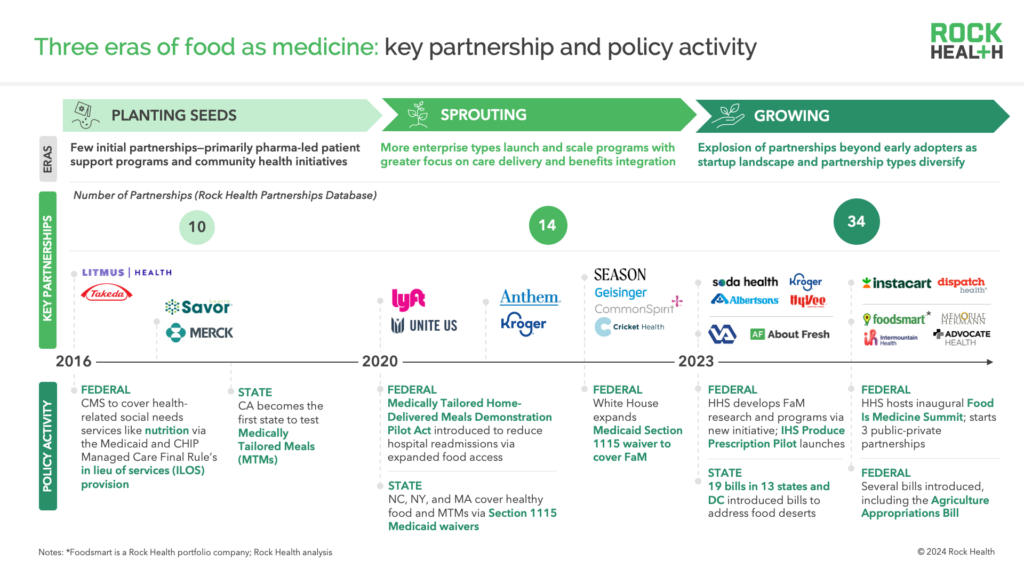

If evolving payer and consumer needs fertilized the market, policy changes planted the early seeds for market growth. As early state and federal FaM policies began to take shape (2016-2019), company partnerships in the space were few (10 from 2016-2019), small in scale, and concentrated among a few early adopter stakeholders (e.g., pharma).

During and post-COVID, new policies expanded Medicaid benefits for food, including use of novel mechanisms (e.g., 1115 waivers) to fund and scale FaM programs like medically tailored meals. As payment infrastructure for FaM began to mature, more (and new types of) businesses including payers, providers, and grocers started experimenting with clinically integrated FaM initiatives. Building on this momentum, activity started to snowball into a flurry of partnerships and program-building by large companies across the healthcare ecosystem. Major White House and HHS commitments to advancing FaM research and programming (e.g., launch of the HHS Food is Medicine Initiative, White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health) have further catalyzed commercial interest in the space.

In the past eighteen months, FaM partnership volume has surpassed that of the prior seven years combined3, many existing partnerships have increased in scale (e.g., nationwide), and new and varied types of companies have entered the arena. These include health systems that have implemented tech-enabled FaM care delivery programs through startups like Foodsmart4 and food retail and tech organizations like Kroger and Instacart that have launched co-branded Medicare Advantage (MA) plans.

Among the companies responding to the emerging FaM opportunity, food retailers have been some of the most active. According to the Food Industry Association, 70% of grocers are expanding their inventory of foods with demonstrated health and nutrition benefits. Retailers are also recognizing the strategic value of offering nutrition services, with some retailers angling to leverage these assets in value-based care delivery models (e.g., Kroger, CVS). More than 80% of food retailers now employ dietitians, and nearly one-third employ dietitians for in-store or virtual consumer support. Plus, retail organizations employ nearly half of all pharmacists, who are one of the most highly trusted healthcare providers and can have frequent, long-term interactions with consumers.

“There is an underestimation of retail assets and components that can actually move the needle in risk-based arrangements for chronic care. We see ourselves at Albertsons Companies as a provider of nutrition solutions that complement the care plan and can be reinforced by our frequent interactions with customers.”

—Irina Pelphrey, GVP of Health at Albertsons Companies

Across the ecosystem, this surge of partnership activity is giving rise to new models in which food access and clinical care are increasingly integrated and financed through federal and commercial payer funding.

Farm to bedside: Mapping the value chain of FaM services

FaM partnerships have evolved beyond the early days of food access-focused programs to a wide variety of nutrition-related services. Below, we highlight three high-level segments of this value chain—food access, nutrition care, and program enablers—each of which contains several distinct components where we see innovation blossoming. Companies achieving rapid commercial scale tend to blend capabilities across these three segments to deliver a more comprehensive, integrated care model (e.g., enable nutrition care and food access).

“Payers are juggling many priorities and want an integrated solution. The players winning RFPs are combining complementary service components to deliver an integrated ‘foodcare’ model—at a minimum, this means enabling personalized telenutrition and sustainable food access.”

—Jason Langheier, CEO & Founder, Foodsmart4

Value chain segment #1: Food access

Food and supply chain

Providers of healthy groceries, prepared meals, and/or digital marketplaces to access third-party food and nutrition products—this group includes grocers, community-based organizations (CBOs), food banks, food delivery partners, food “farmacies” (i.e., markets for fresh and healthy foods where a clinician’s produce prescription can be filled), and digital food marketplaces

Examples: Mom’s Meals, Community Servings, Uber Health, Instacart Health

Service navigation

Services that refer consumers to food access programs and other FaM services, help locate service centers, and support enrollment—often through community organizations with trusted relationships like federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), CBOs, and faith-based organizations

Examples: Findhelp, Unite Us, Pear Suite

Value chain segment #2: Nutrition care

Medical nutrition counseling

Virtual or in-person nutrition counseling with dietitians to provide tailored nutrition plans, recommendations, resources, and continued adherence support

Examples: Foodsmart4, Season Health, Nourish

Behavior change support

Tools for tracking diet and outcomes, accessing educational nutrition content, and receiving recommendations for nutrition-related actions (e.g., generate a grocery basket aligned with a tailored nutrition plan); also includes non-digital services like community nutrition and cooking classes; some digital tools include behavioral economics components (e.g., reward programs to incentivize sustained healthy behaviors)

Examples: January AI, Heali, SeekingSimple

Diagnostics and devices

Technologies that measure and track nutrition-related biomarkers (e.g., microbiomics, metabolomics) and/or related physiological biomarkers (e.g., continuous glucose monitors) to enable individualized nutrition treatment

Examples: Ahara, GenoPalate, Viome, Digbi Health

Provider decision support

Workflow tools that support dieticians and other relevant clinicians with documentation, decision-making, and/or patient follow-up and engagement

Examples: Zenday, Astarte Medical

Value chain segment #3: Program enablers

Fintech

Directed-spend debit cards and vouchers (i.e., category-restricted to healthy products) that enable consumers to use food benefits provided by their health plan

Examples: InComm Payments, Solutran, NationsBenefits, Soda Health

Data and food benefits management

Deep data on consumer purchasing behavior and/or food products (e.g., product-level nutrient data); food benefit management (FBM) services may leverage such data and AI to help payers optimize benefit design, measure program impact, and inform member engagement strategies

Examples: DietID (acquired by Tangelo), NourishedRx, 84.51°

Tech infrastructure

Builder toolkits and software components (e.g., SDKs, APIs) that can be integrated into other FaM solutions or end-to-end solution build services, which may be white labeled (e.g., food product databases, nutrition label scanners)

Examples: Sifter, Innit, DSM

As the FaM market matures, we expect companies to increasingly partner or build new capabilities to stitch together capabilities across this value chain.

Who’s picking up the check?

It seems like a no-brainer that guiding consumers to eat healthier will result in lower healthcare costs and improved outcomes. Given the alignment with payers’ priorities, they should be eager to finance FaM programs—right? It’s not so simple. So what business models are FaM companies cooking up?

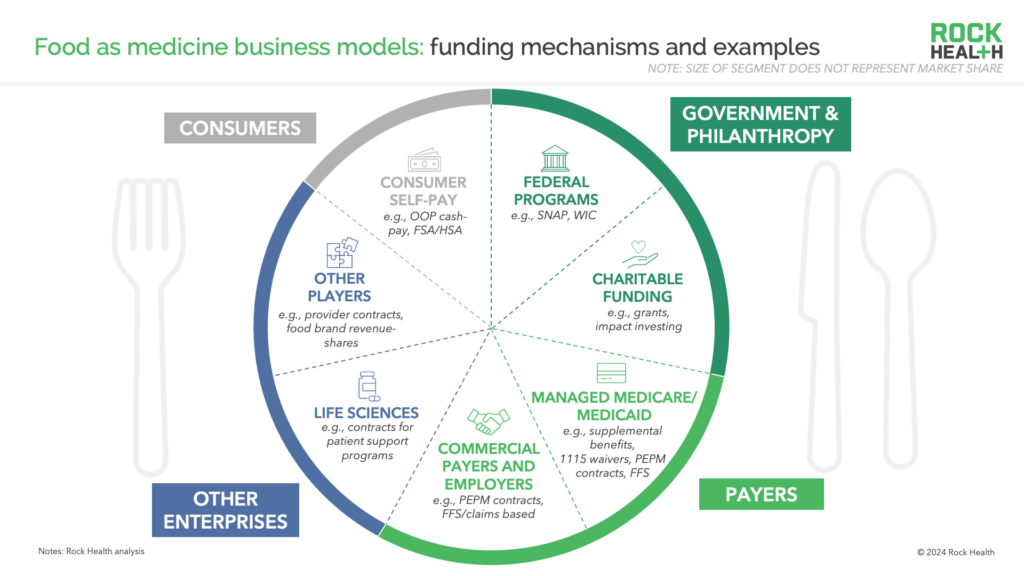

There’s a wide variety of mechanisms for financing FaM offerings, with companies often leveraging a mosaic of several approaches.

In terms of dollars, government programs are the biggest slice of the pie and are largely focused on financing the food supply part of the value chain. Two key programs account for the majority of this FaM financing:

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (fka “food stamps”)—the largest of these—is a $107B program that provides food benefits to 42M low-income Americans

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a $6.7B program that supports 6.6M low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women and their children. In addition to food, WIC funds can be used for nutrition services like education, prevention, and care coordination

Another hearty slice of this pie is filled with payer financing mechanisms, which come in a couple flavors—government-funded (i.e., Medicare Advantage and managed Medicaid) and commercially-funded (e.g., health plans and employers). Key government-funded mechanisms include:

- Medicare Advantage (MA) Supplemental Benefits—nearly 80% of MA enrollees are now in plans that include a meal or food benefit (e.g., stipend for healthy groceries), a historic high and the fastest-growing category of supplemental benefit over the last three years. FaM programs represent attractive levers for MA organizations to acquire and retain members, maximize STAR ratings, and achieve value-based outcomes

- Section 1115 Demonstrations allow Medicaid to provisionally finance state-level programs that advance Medicaid’s goals beyond covered medical benefits. In 2023, following the White House’s guidance, CMS widened flexibility for states to use 1115 demonstrations to address health-related social needs. Covered services include nutrition counseling, home-delivered meals, nutrition prescriptions, and groceries (up to three meals/day, for up to six months)

“Payer funds have traditionally been focused on medically tailored meals but we see increased interest in offering medically tailored groceries and household essentials. Delivery of both meals and groceries are valuable tools to address nutrition security for at-risk populations, like those with mobility challenges and chronic disease, as well as expecting and new mothers. We also see growing activity in using food as a tool for engagement—for example, using food incentives to improve engagement with preventative services and nutrition coaching.”

—Sarah Mastrorocco, VP & GM, Instacart Health

Commercially-funded payer mechanisms—though more limited in scale compared to government-funded ones—are critical components of nearly 40% of FaM companies’ business models1 and are more aligned with the nutrition care segment of the value chain. Notably, these mechanisms are not unique to commercial payers—managed Medicare and Medicaid organizations may also finance FaM services via these mechanisms:

- Payer claims cover FaM services that can be tied to specific coded services in the plan’s medical benefit (i.e., fee-for-service payments on CPT codes). These are common business model components for solutions offering virtual or in-person dietician consults and medically tailored meals

- Payer and employer contracts are typically structured as per engaged member / employee per month (PEMPM) fees. Amid growing payer and employer disillusionment with PEMPM models, some innovators are using risk-based models, linking partial payment to 12, 24-, or 36-month outcomes (e.g., HbA1c reduction)

FaM companies may also generate revenue through direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales or other emerging B2B models, including but not limited to:

- Life sciences contracts, like pharma companies licensing FaM programs to help optimize patient outcomes and experience while on therapy

- Food brand revenue-shares, in which food brands share revenue with FaM companies on upside sales of nutritious products as a result of referrals and recommendations

- Licensing deals with other FaM companies, for example, integrating other FaM companies’ technology as components of the buyer’s broader digital FaM service offering

While payer appetite is growing, behavior change and impact to clinical outcomes from FaM programs can take time. For some payers, this time horizon can complicate the cost-benefit equation when considering member turnover.

“Historically, food is medicine (FIM) has been stuck in the wellness space or in small-scale pilots, but that’s changing with larger scale demonstrations from public and private payers. But we believe that FIM is going to be a benefit like any other in the future. If we were to test it against the criteria used to evaluate new drug therapies, like efficacy and cost effectiveness, it performs just as well. We are moving our research agenda to implementation studies and clinical trials to prove out what interventions work best to improve health outcomes.”

—Cecilia Gerard, Managing Director, Tufts Food is Medicine Institute

As payers develop and mature their FaM strategies, we anticipate growth of this overall pie and its various slices.

What lies ahead

Opportunity abounds in this refreshed landscape, with plentiful options for innovating across the value chain and monetizing through a diverse array of financing mechanisms. Yet challenges remain. Creating the right business model from a complex mosaic of funding sources, separating high-impact, evidence-based partners from the noisy market, and solving operating model and change management hurdles to market entry are all tough nuts to crack. If they can tackle these issues, FaM innovators have a big harvest to reap in this market.

Taking advantage of commercial opportunities in the rapidly evolving food as medicine market requires a deep understanding of the market and a thoughtful strategy—to learn more, reach out to advisory@rockhealth.com.

Footnotes

- Rock Health Venture Funding Database (includes U.S. deals >$2M)

- We use the term “food as medicine” (FaM) for this market primer, given its frequency of use compared to other terms; however, “foodcare” could be an interesting alternative future name for this market to reflect more comprehensive capabilities of innovative solutions in the market (e.g., wraparound care delivery and AI-driven ROI optimization vs. pure food access)

- Rock Health Partnerships Database

- Foodsmart is a Rock Health portfolio company