Women in focus: understanding women as digital health consumers

Women are the “Chief Medical Officers” of their households, primary caregivers from infant to elder care, and top healthcare users. Yet, their health and care needs have historically been overlooked, from clinical research inclusion to product design to care delivery.

Over the past few years, digital health innovators have stepped up to address women+ health needs,1 leveraging new technologies to deliver more personalized, accessible, and affordable digital solutions for women. Amid a surge of national and global initiatives, hundreds of companies have launched related products and programs, and venture funding is following suit. Between 2020 and 2024, U.S. digital health startups offering women+ health solutions2 raised $4.4B in venture funding. In 2024, $671M was invested in digital health startups addressing women+ health needs, accounting for 6.6% of all digital health funding—the highest proportion since 2021.

Women consumers are responding to this surge in innovation as active digital health users. Responses from women in our tenth annual Consumer Adoption of Digital Health Survey show that most women are adopting virtual care, using wearables, and looking to other digital tools to support their health. But within that engagement lies a more nuanced story about how women navigate digital care experiences, where they find value, and which tools are earning their trust.

In this piece, we unpack our latest data on women’s digital health engagement to help guide the next generation of innovation for women—not just by identifying where the gaps are, but by centering how women want to experience care and manage their health.

Understanding women as digital health consumers

According to our 2024 Consumer Adoption of Digital Health Survey,3 women use virtual care and digital health tools at similar, though slightly lower, rates than men. Fifty-six percent of women reported using virtual care4 in the last 12 months, compared to 59% of men. Fifty-four percent of women track at least one health metric (e.g., weight, blood sugar) digitally (the same rate as men), and 52% own at least one wearable or connected device, compared to 55% of men.

At first glance, it appears that there aren’t big differences between women and men as digital health consumers—but diving deeper into the data sheds light on unique ways women engage (or don’t) with the consumer health ecosystem.

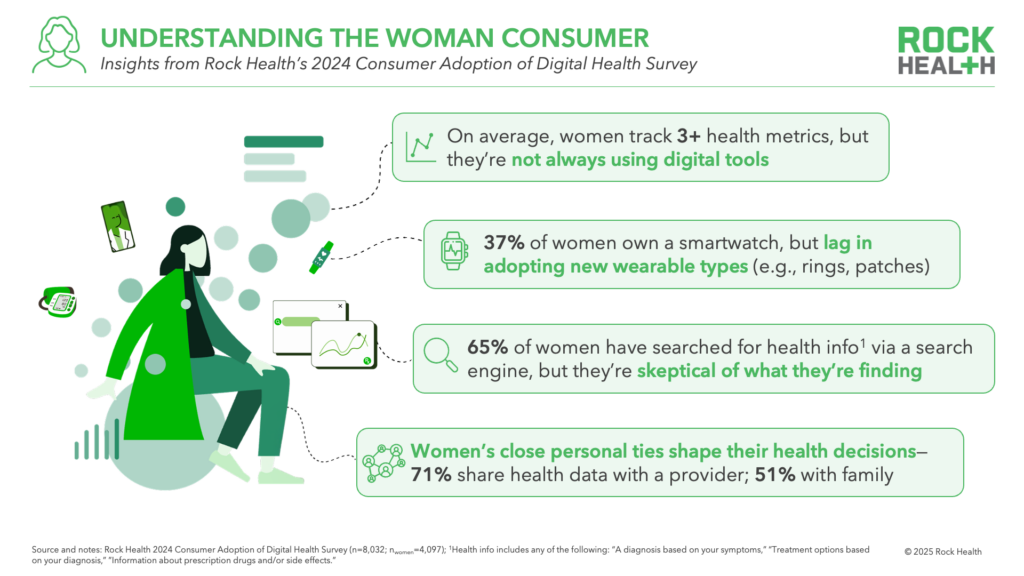

Women are active health trackers—but they’re not always using digital tools

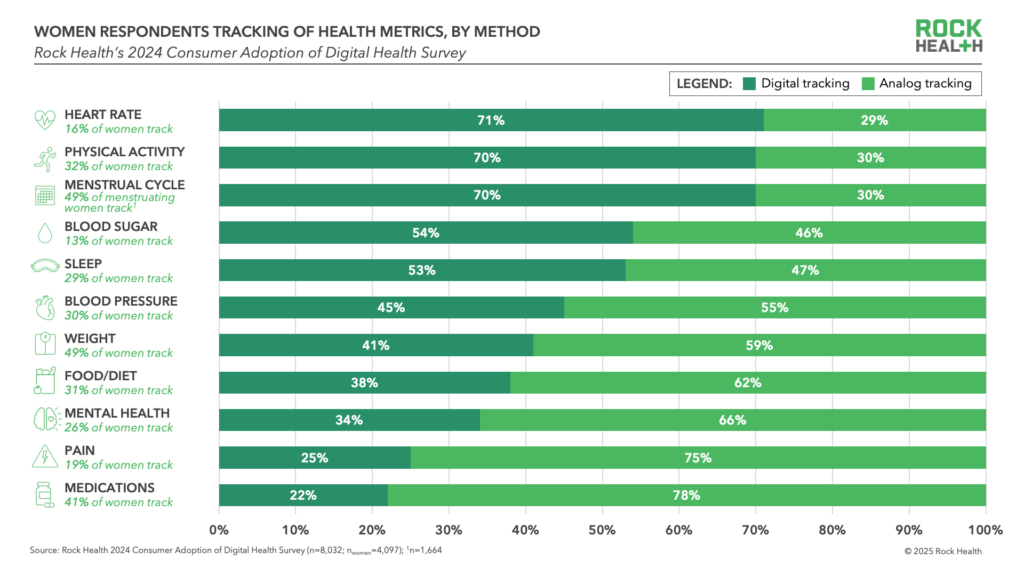

Women keep tabs on their health: on average, women track a greater number of health metrics (3.11 metrics) than men do (2.85 metrics). However, of the metrics they do track, women track fewer metrics via digital means (1.40 metrics) compared to men (1.47 metrics). And women track more metrics via analog methods (1.71 metrics) compared to men (1.38 metrics).

Despite relying more on analog methods overall, women aren’t shying away from digital tracking entirely. For example, 71% of women who track their heart rate do so digitally, as do 70% of women who track their physical activity and 70% of menstruating women who track their menstrual cycles. Digital tracking of these metrics makes sense, as they’re either already incorporated into popular consumer devices (e.g., step counts in smartwatches).

To encourage digital tracking across other metrics, digital solution providers should consider addressing barriers to tracking like clunky data entry, building capabilities around high-value indicators for women, and helping women turn data into useful insights. For example, Oura integrates passive stress monitoring into the Oura Ring’s insight dashboard—a key value-add given how prevalent and deeply impactful stress is on women’s long-term health status.

Beyond smartwatches, women lag in adopting new wearable types

Wearable and health device makers are increasingly building with women in mind. Oura and Whoop have pushed the boundaries in menstrual cycle tracking capabilities, and have added personalization features for women who are trying to conceive or who are postpartum. Wearables are being designed to help women navigate menopause, and there are devices flagging heart disease and complications during high-risk periods in a woman’s life like pregnancy.

Smartwatches stand out as the only type of wearable device5 where women slightly (37%) outpace men (36%) in ownership. Smartwatches are a good proxy for baseline wearable adoption; these devices have been commercially available for 10+ years, offer multi-purpose features beyond health (e.g., phone calls, notifications, payment), and are even available at a discount or free under some Medicare Advantage plans.

Among emerging wearables like rings or patches, women lag in adoption compared to men—notably, among smart rings. Only 5% of women reported owning a smart ring, compared to 9% of men, despite the fact that smart rings are often marketed toward (or even made for) women, with some smart ring makers publicly committing to improving women’s health and wellbeing. We’ll be watching closely to see how this dynamic evolves, especially as tailored partnerships between ring makers and women’s health apps grow. Advancements in novel wearables like hormone tracking patches could also provide more tailored solutions for women’s unique health needs.

Women are searching for health information online, but they’re skeptical of what they’re finding

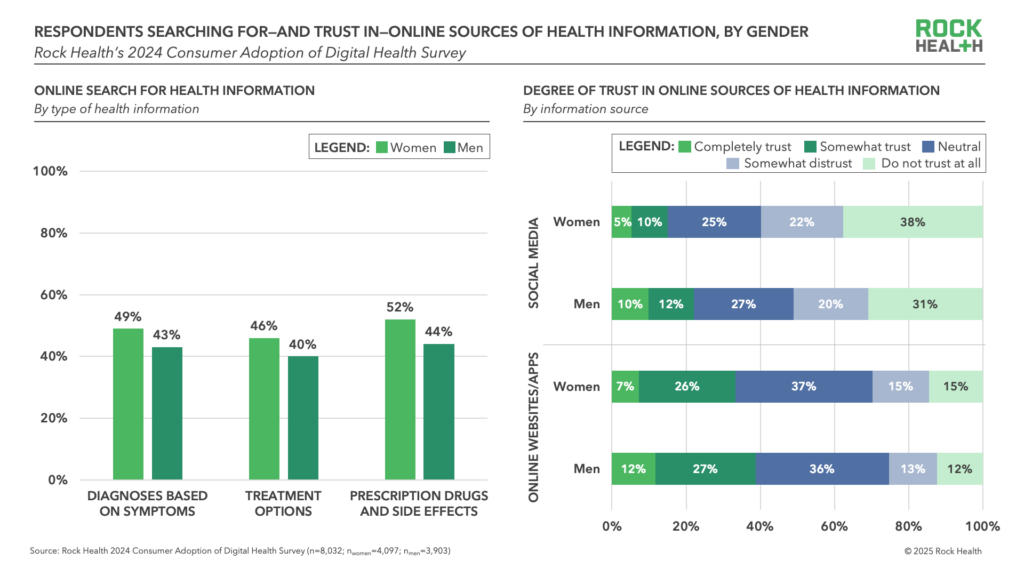

We know that women actively use the internet when it comes to researching their health. Women of all ages search for health information on Reddit and join online condition affinity communities, while Gen Z and Millennial women are particularly likely to browse social media throughout the day (often following health influencers). Our Survey data shows that more women than men use search engines like Google and Bing to research a wide range of health topics, from diagnoses (49% of women vs. 43% of men), to treatment options (46% vs. 40%), to prescription drugs and side effects (52% vs. 44%).

Even though women are looking for health information online, there’s an interesting disconnect—they don’t necessarily trust what they find. Just 7% of women “completely trust” health information from websites and apps (vs. 12% of men), and 5% of women “completely trust” health information from social media (vs. 10% of men).

The chasm between women’s online health information-seeking behavior and their trust in that information suggests that women are wary of misinformation and potentially influenced by unique factors related to online women’s health information (e.g., suppression by advertising platforms, removal of information from federal agency websites). The challenges women face in accessing high-quality online health information can negatively impact their experiences with AI tools, too. Despite being search engine super-users, women have been slower to adopt AI tools like ChatGPT when looking for health information (15% compared to 23% of men). While search engines let users compare and judge multiple sources’ credibility for themselves, AI’s packaging of information into single synthesized answers may feel less verifiable and undermine adoption.

With the usage versus trust disconnect in mind, there is opportunity for health innovators to continue creating reliable, evidence-backed, health information and ensure access in online spaces and digital experiences, where women are already looking.

Women hold close relationships with providers and family—and that impacts their health behaviors

Women’s tight-knit connections—with family, friends, and their communities—naturally carry over into how they handle their healthcare. Many take on caregiving roles (34% of women in our Survey are caregivers of a child and/or loved one) and often juggle their own health needs alongside their family members’. That sense of connection extends to their health data: over half of women (51%) say they’re willing to share health data with family members, a rate six percentage points higher than men. Seventy-one percent say they’re willing to share key health information like medical records, test results, and activity data with their healthcare providers, compared to 62% of men—and this number increases significantly in older generations.

This willingness to share may reflect how deeply women value trusted relationships in managing their health—whether that’s with a clinician they’ve seen for years or a family member supporting them through a diagnosis or life transition. As data-sharing standards like FHIR make it easier to move information across platforms, there’s growing potential to design tools that match women’s preferences for more connected care experiences.

Some startups have picked up on this relational dynamic, designing platforms that allow families to access mental health care together or building care teams that collaborate across modalities and life stages. These models reflect an important throughline: for many women, strong relationships—whether with loved ones or care teams—aren’t just a preference. They’re a central part of how they manage their health.

Designing a digital health future that works for women

This is only the beginning of understanding what women want and need as healthcare consumers—the data here only scratches the surface. Women aren’t a monolith, and their behaviors aren’t uniform and neither are their needs. A whole host of factors, including age, socioeconomic status, caregiving responsibilities, geography, and comfort with technology all shape how women navigate the healthcare system and choose tools that fit their lives.

Rather than aiming for universal adoption, the opportunity lies in delivering the right solutions to the right people—meeting women where they are with tools that feel relevant, trustworthy, and supportive. That means digging deeper into consumer research by asking women what they want and building with nuance.

As innovators, investors, and healthcare leaders, we have a clear opportunity: to design a digital health ecosystem that reflects the realities of women as healthcare decision makers, caregivers, and patients.

Wondering what it truly means to design for women+ digital health?

We are, too—and we’re diving in alongside innovators, investors, researchers and advocates to unpack the opportunities and challenges. Together we’re exploring questions like:

- What do inclusive, whole-person solutions for women actually look like in practice and how can we raise the bar to support women navigating care and decision making?

- How do we drive more investment toward women+ health innovation?

- What will it take to increase adoption of women+ health solutions across underserved communities?

We are passionate about driving ecosystem change in untapped areas of healthcare, where market opportunities exist and technology has the power to create meaningful health advancements. Let’s explore what’s possible together. Whether you’re looking for strategic insights, data-driven analyses, or collaborative ways to build toward a better future, we’d love to connect and identify how we can partner for impactful change.

Tap into insights and strategic guidance for enterprise companies with Rock Health Advisory.

Get in touch with the venture team at Rock Health Capital.

Join us in advancing ecosystem change at RockHealth.org.

And last but not least, stay plugged into the Rock Health community and all things digital health with the Rock Weekly.

Footnotes

- Rock Health uses the term “women+ health” to encompass the full spectrum of health needs experienced by cisgender women, as well as transgender individuals, nonbinary individuals, and others whose health needs relate to those of cisgender women. Throughout this piece, we also use the term “women” to specifically refer to respondents in our Consumer Adoption of Digital Health Survey who identify as women.

- Startups offering women+ health solutions include companies focused specifically on women+ health (e.g., Maven Clinic) as well as those with broader offerings that include one or more solutions tailored to women (e.g., Koios Medical).

- Survey respondents (n=8,032) are Census-matched by gender, age, U.S. region, race/ethnicity, and annual household income. The Survey was administered from November 1, 2024 to December 3, 2024. Respondents used their personal desktop, laptop, smartphone, or tablet to complete the Survey in English.

- Virtual care modalities include “live video,” “live phone, “text message (SMS), app, or website-based messaging.”

- Wearable form factors included in the survey: “smart watch (e.g., Apple watch, Fitbit),” “Smart ring (e.g., Oura, Ultrahuman),” “Continuous glucose monitor (CGM) (e.g., Dexcom, FreeStyle),” “Smart scale (e.g., Withings),” “Connected blood pressure cuff (e.g., Withings, Garmin),” “Other (e.g., smart patch, smart toilet)”.