Why there is no Uber for healthcare

At last year’s summit, Rock Health hosted a panel on the “uberification” of healthcare, with senior leadership from Doctor on Demand, Pager, and Studio Dental discussing the challenges and opportunities of reinventing traditional in-person medical visits. Major news outlets, including The Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and Fortune, subsequently released stories on the potential of “on-demand” healthcare. Whether consumers are excited about having on-demand healthcare services or the industry is hopeful for cost savings associated with better supply and demand matching, the “Uber for healthcare” has become the elusive unicorn. And now, Uber itself is getting into the game, partnering with multiple healthcare companies to literally launch Uber for flu shots. The company also plans to integrate its platform with providers so that patients can simultaneously book and arrange rides for their healthcare appointments. As a result of this growing spotlight on on-demand healthcare, we are left wondering: can there really be an Uber for healthcare?

Background

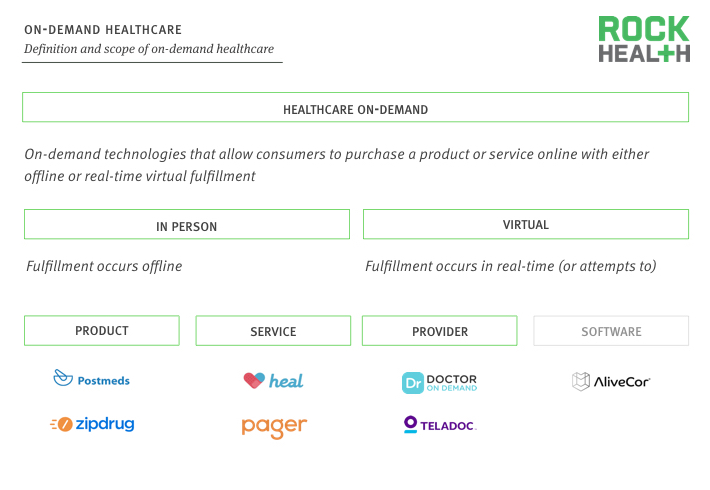

On-demand healthcare companies provide telemedicine, house call, and medication delivery services.

Source: Company websites

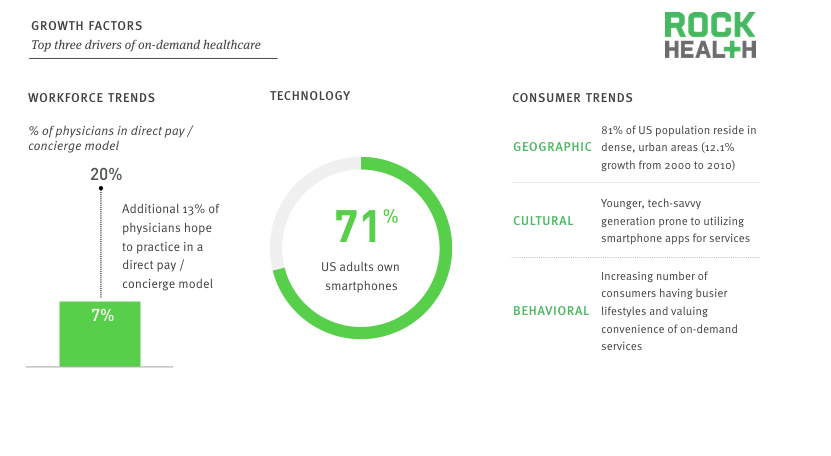

On-demand healthcare companies allow consumers to purchase a product or service through a web-based or mobile channel with either offline or virtual fulfilment. Offline fulfilment includes both product and service delivery, with companies such as Postmeds and Pager delivering medications and sending healthcare providers, respectively, directly to consumers’ homes and workplaces. In contrast, online fulfilment occurs when a consumer is virtually connected with a healthcare provider or software tool to diagnose a health condition.

This research focuses on on-demand healthcare that requires human resources for product and service delivery rather than automated algorithmic diagnosis, which is a nascent space facing different types of challenges.

Landscape

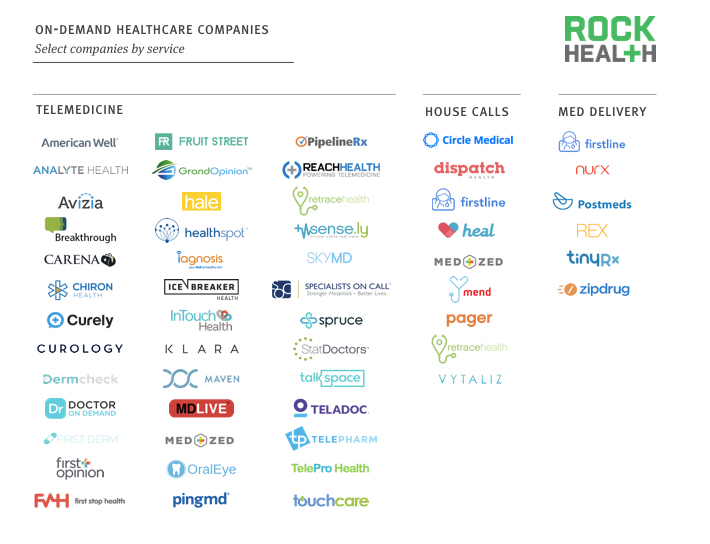

The majority of on-demand healthcare companies are in telemedicine, although a growing number of startups are offering house calls and medication delivery.

Note: Select companies displayed; list us\ not exhaustive

Source: Company websites

On-demand healthcare companies tend to build their core competence in a single space before offering additional services (i.e., starting with house calls and adding on medication delivery). Even within these core areas, some companies choose to further specialize. This likely is viewed as a strategic entry point for companies to build a strong brand and ensure proof of concept within a particular population segment or for a specific service type before scaling their business. For example, SkyMD and DermCheck only provide telemedicine services for dermatology—a specialty that is attractive due to its ease of delivery through video consultations and the ability to offer a lower cost alternative to traditional, high-margin office visits. As the niches become more crowded, these companies may aim to expand their portfolio of services to continue to gain market share and transaction volume.

For house calls, while companies such as Vytaliz provide acute care services in addition to offering flu shots and performing lab tests, others (e.g., Pager) focus on urgent care. Similarly, on-demand medication delivery companies may choose to deliver only certain medications (e.g., Nurx only offers birth control prescriptions). Although this specialization initially results in increased fragmentation of the on-demand healthcare market, over time, the “winners” that emerge will be the companies that offer all-around best-in-class solutions and are able to successfully scale.

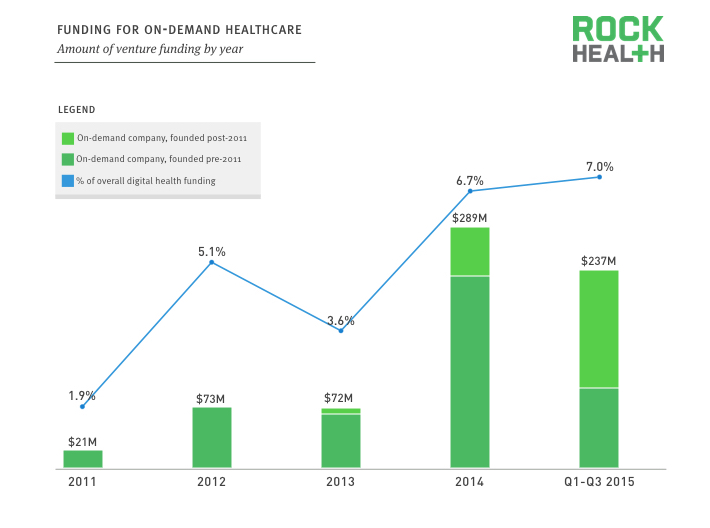

Funding for on-demand healthcare has continually increased, with a total of $692M in funding since 2011.

Source: Rock Health Funding Database

Funding for on-demand healthcare has been steadily growing, representing over seven percent of total digital health funding, up from less than two percent in 2011. On-demand healthcare companies saw 300 percent year-over-year funding growth in 2014, compared to 114 percent growth during this same period for funding across all of digital health. While telemedicine has historically received much of the funding dollars, house call and medication delivery companies have recently seen an increase, with TinyRx, Zipdrug, and PediaQ all having raised capital in just the last month.

Note: Companies founded prior to 2011 that were not “digital” by origin, such as Teladoc and American Well, accounted for 20 percent of on-demand funding in 2015. For example, an overwhelming majority of Teladoc’s visits are done over the phone. Through the first three quarters of 2015, on-demand companies founded after 2011 received 60 percent of all funding dollars.

Healthcare companies are attempting to capture the new demand that comes from workforce, technology, and consumer trends.

Several factors explain the increase in the number of on-demand healthcare companies. First, physicians are becoming more interested in flexible work schedules and in practicing direct-pay or concierge medicine. On-demand companies providing house calls and telemedicine services that recruit healthcare providers and pay them a portion of the service fee can capitalize on these supply-side trends. Secondly, consumer cultural and behavioral trends provide telemedicine, house call, and medication delivery companies with the potential promise of an early adopter population that could drive market uptake. The growing number of individuals living in dense, urban areas also allows for an easier, more cost-effective way to service consumers (i.e., multiple deliveries in a fixed geographic radius). Additionally, smartphone adoption and the availability of low-cost technologies (e.g., MEMs and sensors, low-energy Bluetooth) have enabled a fairly convenient and inexpensive way to connect the supply and demand sides of the healthcare economy, making on-demand services accessible to the mass market.

Moreover, tailwinds from the ACA continue to help drive digital health adoption. With the individual mandate, the increase in insured consumers has created demand for more access to healthcare providers and services. But perhaps more simply, the growth in on-demand healthcare can be tied to the “uberification” of the economy. On-demand mobile services have pervaded nearly every consumer-facing sector, including home services (e.g., Handy), food (e.g., Munchery, Grubhub), and transportation (e.g., Uber, Lyft). In this age of consumerization, expectations have been created around the consumer experience, including instant gratification and immediacy of fulfillment, which are now bleeding into healthcare as well. Consequently, the “uberification” of healthcare seems to be the next quest for many entrepreneurs who are vying for a slice of this three trillion dollar industry.

Challenges

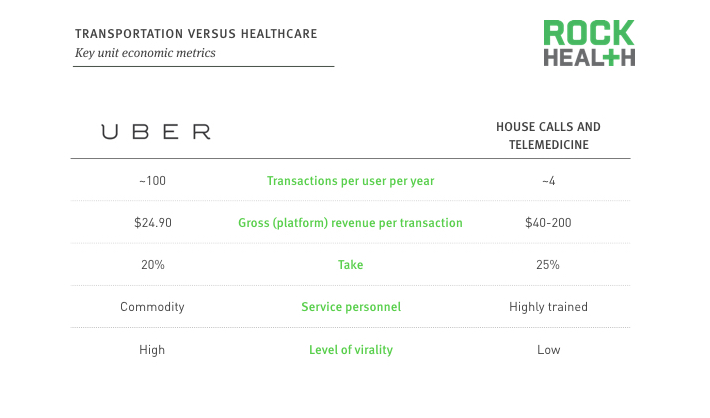

The unit economics are far more challenging for on-demand healthcare versus other on-demand sectors, with transportation as an example.

Source: Uber economics, Company websites

When taking a direct-to-consumer approach, the significantly lower ratio of customer lifetime value to customer acquisition cost makes the unit economics in healthcare far more challenging than other on-demand sectors, such as transportation. In contrast with Uber’s high number of transactions per user per year, on-demand healthcare companies have, on average, very few interactions with their customers on a regular basis (think: average number of physician visits in the US is only four a year). This decreases customer lifetime value since the higher per-transaction revenue fails to compensate for the significantly lower number of transactions per year. Additional problems stem from the lack of virality in healthcare. Consumers are less willing to openly discuss and share their healthcare experiences, which impedes organic consumer awareness and raises the cost of customer acquisition.

Also, consumers are less willing to pay out-of-pocket for their healthcare expenses compared to other types of services. According to our landmark national consumer survey, while almost one-third of internet-connected adults in the US strongly agree that they are actively taking care of their own health, only seven percent strongly agree that they are willing to pay out-of-pocket for their healthcare expenses. The inability to raise prices in a price-sensitive consumer market and the high labor costs for highly trained healthcare personnel lowers unit margins.

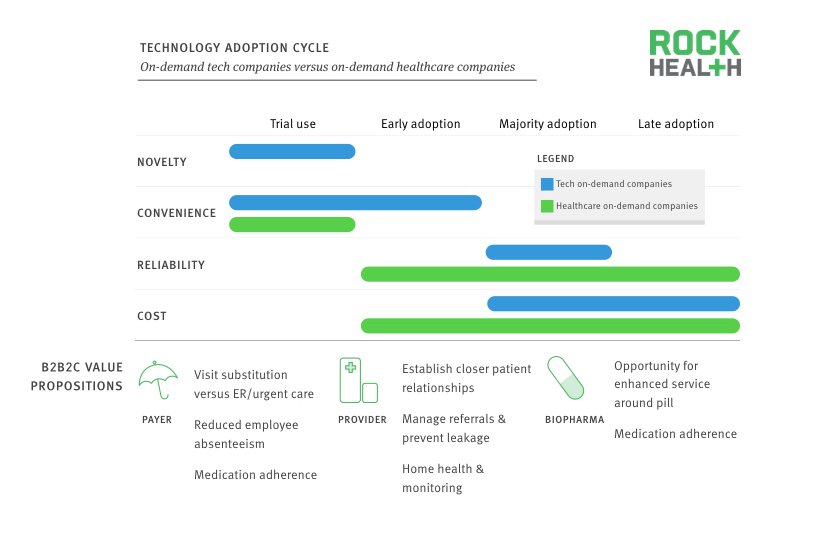

On-demand healthcare faces a very different technology adoption cycle, driven more by reliability and price than novelty and convenience.

Most on-demand technology companies are able to rely on the novelty of their services to pique the interest of “trial” users and continue acquiring customers primarily by offering convenience. Further market uptake occurs when the service proves to be reliable at an “affordable” price point. In contrast, the stakes are much higher in healthcare—receiving broken eggs from a grocery delivery service is not the same as receiving an incorrect diagnosis for pneumonia. Consequently, consumers are much more concerned with ensuring care quality prior to adoption and are less likely to use on-demand healthcare services solely for the appeal of novelty and convenience. The resulting catch-22—alleviating consumer concerns around service quality and reliability requires greater consumer awareness and higher utilization rates—imposes significant growth hurdles. Low willingness to pay out-of-pocket for healthcare expenses, as discussed above, also slows market adoption. In today’s environment, even early adoption requires coverage through third parties such as insurers and self-insured employers.

Considerations

Faced with steep CACs and low willingness to pay, established on-demand companies have pivoted to B2B for distribution, necessitating stronger value propositions.

Low consumer willingness to pay forces on-demand healthcare companies to seek alternative payment models. In an effort to lower customer acquisition costs and expedite market uptake, many companies are shifting to a B2B2C business model where the middle “B” plays a key role in distribution and reimbursement. HealthTap recently announced their newest offering, Compass, to target employers and Dispatch Health has partnered with Centura Health. Striking such partnerships necessitates strong value propositions oriented around financial ROI (e.g., cost savings for health systems and payers by driving up medication adherence or reducing the number of high-cost emergency room visits).

Moreover, such partnerships also allow for better integration into the patient care continuum, which may be key to capturing a more sizeable portion of provider and pharmacy interactions and replicating some of the success seen to date with retail clinics. Aided by the high foot traffic of retail pharmacies, retail clinics have been able to coordinate care with health systems by helping fulfill physician oversight requirements and managing chronic care patients—there are at least 100 partnerships between retail clinics and providers. With near universal coverage from payers (e.g., 84% of visits to CVS clinics were paid for by third parties), retail clinics have been able to take consumer cost concerns off the table and leverage their convenient location and little-to-no wait time to drive utilization. Still, as retail clinics become more integrated into the care continuum, new challenges have arisen that must be addressed, such as adhering to standardized clinical protocols and implementing interoperability infrastructure to ensure data is shared with the physician and care team.

The most common B2B2C model used by on-demand healthcare companies (e.g., Teladoc) is one where intermediaries pay a per-member per-month (PMPM) fee regardless of utilization. However, as the industry focuses on value-based care and cutting costs, some on-demand healthcare companies (e.g., Doctor on Demand) are taking on the risk and charging based on utilization. In this latter model, intermediary businesses often do not incur costs unless ROI thresholds are met or consumers actually use the service. The onus is on on-demand healthcare companies to enable user engagement in order to generate revenue and deliver cost savings. As a result, while B2B2C distribution necessitates delivering financial ROI, on-demand healthcare companies—by offering a high-quality, preferred consumer experience—must also be able to show that consumers will, and want to, use their services. Identifying the most value-added use cases will be key to not only demonstrating the ROI benefits but also driving adoption. For instance, house call companies should work closely with distribution partners in order to promote adoption in target populations (e.g., elderly, maternity) that could benefit most from in-home services.

The promise of telemedicine, house calls, and medication delivery to reduce healthcare costs and improve outcomes has undoubtedly caught the attention of providers, payers, and self-insured employers. But because of the unique unit economics hurdles in healthcare and the need to both demonstrate financial ROI to distribution partners and cater to consumer quality concerns, the path to building a successful on-demand business is likely longer and more complex than originally hoped.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ophelia Brown (Index Ventures), Julie Papanek (Canaan Partners), and Blake Wu (NEA) for taking their time to share insights about the challenges and opportunities facing on-demand healthcare.