To track or not to track? How digital period tracking may change in a post-Dobbs world

In June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, revoking the constitutional right to abortion and overturning the previous legal precedent of Roe v. Wade. The ruling opened the door for states across the nation to criminalize abortion care within their jurisdictions, gravely impacting care delivery efforts and health equity for women+1 and birthing people within the United States.

Post-Dobbs laws criminalizing abortion care could carry serious implications for consumers who discuss or track their health digitally. In one recent example, authorities in Nebraska—a state which has outlawed abortions after 20 weeks of gestation—subpoenaed and were granted access to Facebook messages between a mother and her 17-year-old daughter as evidence to charge them with carrying out a criminal abortion.

Reproductive experts have expressed particular concern for individuals using digital health tools such as apps, wearables, or digital journals to track their menstruation and fertility—behaviors referred to colloquially as “period tracking.” Such data could signal a pregnancy and may be combined with other data sources (e.g., location data, medical claims data, paid time off logs) to infer if a person is currently seeking out abortion care. Whether subpoenaed by law enforcement or transferred by data brokers to authorities, these digital records risk putting consumers in potentially dire legal or criminal situations.

Every year, Rock Health surveys nearly 8,000 adults about their digital health behaviors, including their use of digital trackers for menstruation and fertility. In this piece, we review data from our 2021 Consumer Adoption Survey to establish a baseline of U.S. consumers’ digital period tracking behaviors prior to the Dobbs decision and explore the following questions:

- How and to what extent have individuals across the U.S. digitally tracked their periods?

- How might digital period tracking change following the Dobbs decision?

- How can digital health founders, investors, and enterprise leaders review their approaches to health data management, specifically reproductive health data management, at this moment?

While we don’t have concrete answers now to how consumer digital period tracking behaviors may change, we hope this piece seeds perspectives and sparks questions for those who collect and work with sensitive health data. And of course, we’ll be following up on changes in consumer behavior with the upcoming release of our 2022 Consumer Adoption Survey data.

Survey methodology

Since 2015, Rock Health has annually surveyed U.S. adults to track consumer adoption of digital health technologies. Rock Health’s 2021 Digital Health Consumer Adoption Survey (hereinafter referred to as the “Survey”) was completed in August 2021 amongst a U.S. Census-matched sample of 7,980 adults.2

Of the 7,980 total respondents, 4,098 respondents reported currently experiencing or having ever experienced a menstrual cycle.3 To understand the behaviors of adults with a current menstruation cycle, for this analysis, we focus on respondents between 18 and 54 years of age, as the average US menstruating individual experiences menopause (and stops menstruating) at age 51.4 This age-bound menstruating cohort (hereinafter referred to as “menstruating respondents”) includes 3,054 respondents and approximates the number of Survey respondents who currently menstruate.5

In 2021, who tracked their period digitally?

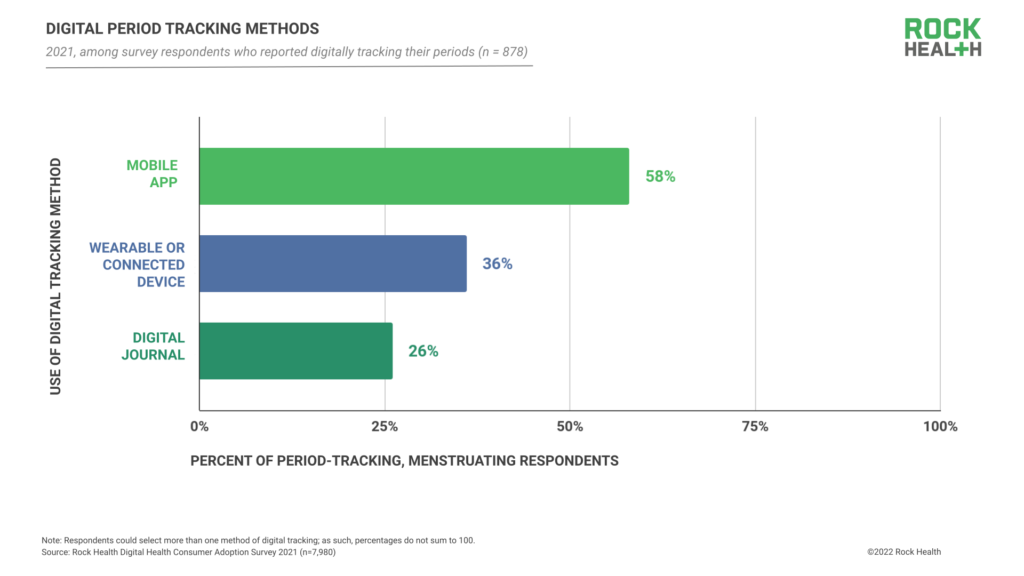

In 2021, 878 respondents (29% of menstruating respondents) reported using at least one digital product or solution to track their menstruation and/or fertility, which we refer to as “period tracking” throughout this piece. Of these 878 respondents, 36% reported using a wearable or connected device, 58% reported using a mobile app, and 26% reported using a digital journal.6

We also analyzed period tracking rates among specific demographic groups, to gain an understanding of which segments of menstruating respondents are using digital period tracking the most (and least). Here’s what we found:

- Age: In our 2021 Survey, younger menstruating respondents reported greater use of digital period tracking solutions when compared to respondents in older age brackets. Of menstruating respondents aged 18-24, 42% used a digital means to track their periods, compared to 33% of respondents aged 25-34, 26% aged 35-44, and 16% aged 45-55.

- Gender identity: Of the Survey’s menstruating respondents, 79% identified as women and 30% of those female menstruating respondents reported digitally tracking their periods. Notably, 19% of menstruating respondents identified as men, 24% of which reported digitally tracking their periods. For menstruating respondents who do not identity as women but were assigned female at birth (AFAB), period tracking can support an individual in anticipating their patterns of gender dysphoria (when a person experiences distress due to a mismatch between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity) brought on by menstruation, or monitoring the effects of gender-affirming hormone therapies (GHT).

“Queer people are often left out of the abortion conversation. Transgender people may be digitally tracking their period to prevent pregnancy or to track ovulation to try to become pregnant. For trans and non-binary people, a period can be a constant reminder of a bodily function you don’t want or a procedure you may not be able to afford. It can be better to know when a period is coming and to not be caught off-guard. Period tracking can be self-care.”

– Dr. Myeshia Price, Director of Research Science, The Trevor Project

- Race and/or ethnicity: Rates of digital period tracking were relatively similar across respondents of different races and ethnicities. Thirty-eight percent of Hispanic or Latina/o/x menstruating respondents, 35% of Asian menstruating respondents, and 30% of Black menstruating respondents reported digitally tracking their periods. Twenty-seven percent of menstruating respondents who identified as white-only reported digital period tracking, and 25% of American Indian or Alaska Native respondents reported digitally tracking their periods.7

- Household income: Overall, the percentage of menstruating respondents who reported digitally tracking their periods ranged from 24-33% across all household income ranges. Notably, 24% of menstruating respondents reporting a household income less than $25,000 digitally tracked their periods, which may relate to the financial costs of digital device ownership and connectivity.

- Rurality: Of menstruating respondents who reported digitally tracking menstruation or fertility, rural respondents reported the lowest rates: 32% of suburban respondents, 28% of urban respondents, and 23% of rural respondents reported digital period tracking.

- Insurance coverage: The percentage of menstruating respondents who reported digitally tracking their periods was similar across types of insurance coverage, though privately insured respondents reported the highest rates of tracking. Of the Survey’s menstruating respondents, the digital period tracking rates are: 26% of those insured through state-based ACA exchanges, 27% of those insured through Medicaid, and 31% of those with private insurance (purchased insurance through an employer or directly from a health plan).

How might digital period tracking patterns change in 2022 and beyond?

In light of Dobbs, consumers using period tracking apps may find themselves in a Catch-22. While digital health tools might help consumers prevent an unwanted pregnancy, if challenges arise and abortion care is sought, data generated from these tools may be used against them.

As such, it’s difficult to predict how consumers’ digital period tracking behaviors will change in the back half of 2022 and beyond. While some consumers have already opted to delete digital period trackers post-Dobbs, certain period tracking apps reported significant upticks in downloads (though, in some cases, this may relate to consumers switching between digital products). It’s also possible that many menstruating individuals may not be aware of (or presently concerned by) the changing risks of digital period tracking and will not adjust their behavior.

In addition to watching for broad shifts in digital period tracking, we’ll be watching to see how tracking behaviors change across respondents of different ages, genders, races and/or ethnicities, ruralities, income ranges, and insurance statuses. We’re especially interested in how digital tracking behaviors may differ based on respondents’ state of residence. For menstruating respondents who live in states that have legally limited or are at risk of legally limiting access to abortion care following the Dobbs decision, both the promise (e.g., family planning support) and risks of digital period tracking are heightened, as associated health data may be used for future civil or criminal indictments.

“Who gets criminalized when digital health information is weaponized? Digital health companies must consider how reproductive oppression has operated in this country for Black women, immigrant women, poor women, and other birthing people. There are ways in which this moment will worsen the tendency to criminalize certain groups as opposed to others. As different products and innovations come to market, I worry about what will result if these considerations are not made.”

– Erika Seth Davies, CEO, Rhia Ventures

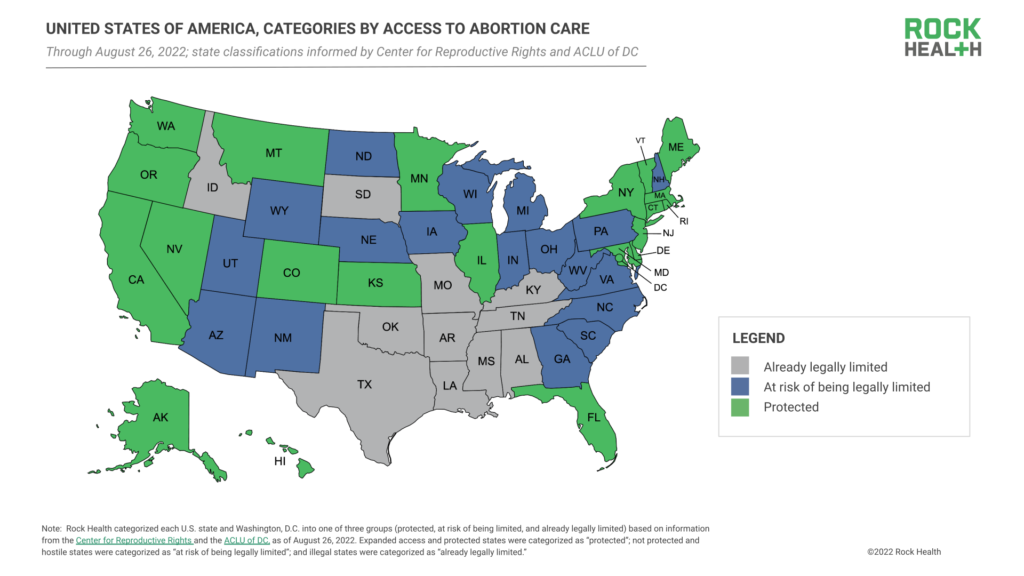

Adapting research from the Center for Reproductive Rights and the ACLU of DC, we have categorized each U.S. state and Washington, D.C. into one of three groups: (1) states where abortion care is protected, (2) states where abortion care is at risk of being legally limited, and (3) states where abortion care has already been legally limited or completely outlawed following the Dobbs decision.8 Analyzing our 2021 Survey data, we established that, prior to Dobbs, 30% of menstruating respondents who live in currently-classified “protected” states (at the time of writing), 29% of menstruating respondents living in states where abortion care is now at risk of being legally limited, and 25% of menstruating respondents living in states where abortion care is now legally limited reported tracking their periods digitally.

In 2022 and beyond, we may see digital period tracking behaviors subside in states where access to abortion care is already legally limited or at risk of being legally limited, given the heightened risks associated with reproductive health data in these jurisdictions. This may further exacerbate digital health equity gaps across the nation, as affected communities’ comfort with using digital tools wanes and their representation in digital health solution advancement (e.g., representation in consumer studies or AI training datasets) dwindles.

Insights for founders, investors, and enterprise healthcare leaders

Digital health startups in the period tracking space are already feeling and responding to Dobbs’s effects on consumer behavior. Popular period tracking app Clue, which is based in Europe, saw a 2,200% increase in app downloads after it stated that its app data is protected under European data privacy laws and could not be subpoenaed by the U.S. Period tracking app Flo launched “Anonymous Mode,” a setting that allows individuals to use the app without disclosing any personally identifiable information.

Given that Dobbs may establish a dangerous precedent for health surveillance, data privacy and security may rise as consumer priorities—impacting consumer use of digital health products and solutions across therapeutic areas. For any healthcare leader building, managing, or distributing data-tracking digital tools, now is the time to explore privacy and security enhancements including end-to-end encryption, deidentification of data by bulk processing, edge computing, local differential privacy, and privacy by design. Wise investors are checking in with their portfolio teams on data privacy and protection improvement roadmaps, particularly in therapeutic areas where secure digital health solutions are nascent or critically needed, such as reproductive care.

“The Dobbs ruling puts a spotlight on period-tracking apps as a question of healthcare data tools more broadly: who really owns an individual’s health data? For enterprises, startups, investors, and consumers, we are being presented with both an opportunity and a challenge as data sharing policies shift from being concerned with competitive advantages between players to being patient-centric and safety-oriented.”

– Peter King, Mobile Product Executive

We encourage enterprise healthcare leaders to consider the following questions—we expect them to increasingly come to the forefront given the intertwined nature of health data, care delivery and coverage, and digital innovation.

For leaders at provider organizations:

- How might data tracking concerns impact patients’ willingness to participate in digital biomarker tracking or remote monitoring programs, or engage with providers via telemedicine—especially in sensitive arenas such as OB/GYN care?

- If our organization provides virtual care delivery across state lines, how might patients’ comfort and safety within digital interactions change based on their state of residence?

For employee benefits managers and health plan leaders:

- How might current digitally-enabled benefits (e.g., virtual employee-assistance program (EAP) consultations, virtual appointments, wearable health tracker programs) put our employees or members at risk for sensitive data leaks or having their data subpoenaed?

- Do our digital health benefits offerings (our own and our vendors’) have enhanced data privacy and security features? What screening measures and benchmarks could be implemented to ensure our solutions follow best practices?

For life science and research leaders:

- If clinical trials involve health data tracking (including, but not limited to, period tracking), how might patient willingness to participate in research change?

- What types of device updates and patient education tools are needed to ensure high-quality data collection that balances participant data protection?

- If certain communities reduce or discontinue data collection as a result of privacy and security concerns, how will research data be skewed? Which patient communities are at risk of becoming data-underrepresented in population health research and clinical trials?

For leaders at medical device manufacturers and consumer technology companies:

- What product features are needed to support data privacy and consumer control? Will these controls be a default addition or a choice to opt in or out?

The forces driving future changes in consumers’ period tracking behaviors will have reverberating effects across healthcare—including broad impact on the future of health data collection, data privacy, and the care delivery and research models that rely on that data. We are committed to tracking and reporting on these sector, societal, and consumer shifts, all of which will continue to offer healthcare leaders important signals to guide digital innovation decisions—both to ensure market success as well as long-term patient protections.

+ Beyond data, there’s discourse. We’re honored to have had the opportunity to hear from several prominent experts in women+ health regarding how digital health can support the actions of policy advocates, organizers, clinicians, and health educators to address the needs of those most impacted by the repeal of Roe v. Wade. Click here to tune into a virtual Rock Health Summit 2022 panel featuring Dr. Michele Goodwin, UC Irvine; Erika Seth Davies, Rhia Ventures; Dr. Megan Ranney, Brown University; Kate Ryder, Maven Clinic, and moderated by Jennifer Yoo, Fenwick & West LLP, as they unpack how digital health can show up as the implications of the Dobbs ruling continue to unfold.

For healthcare leaders interested in further discussing health data privacy and safety in the context of digital health innovation, please reach out to advisory@rockhealth.com.

Footnotes

- Rock Health uses the term “women+” to encompass the full spectrum of health needs experienced by cisgender women and other individuals whose health needs relate to those of cisgender women but identify as transgender or nonbinary.

- Respondents used their personal desktop, laptop, smartphone, or tablet to complete the Survey in English. While the Survey methodology lends to the undersampling of non-English speakers and those without digital devices or reliable internet connectivity, we present this data as a starting point for broader consumer behavior conversations and avenues for future research.

- Data reflects responses to the question asked to all respondents, “Do you currently have or have you ever had a menstrual cycle? Select one answer.”

- Age 54 was selected as the age cutoff given that it was the upper limit of the 44-54 age group in the Survey age categorizations. Respondents under the age of 18 were disqualified from the Survey, though many period tracking apps do not institute 18+ age requirements.

- Note: menstruation does not necessarily indicate fertility, as there may be other factors that contribute to fertility.

- Because respondents could select more than one digital tracking solution, percentages in this breakdown do not sum to 100 percent.

- Respondents could select multiple racial/ethnic categories. Sample sizes were small for menstruating respondents who identified as Hawaiian Native or Pacific Islander (n=48) or selected “Other” (n=21); therefore, these cohorts of respondents are not listed.

- U.S. states and Washington, D.C. are categorized into three groups (protected, at risk of being limited, and already legally limited) based on information from the Center for Reproductive Rights and the ACLU of DC, as of August 26, 2022. Expanded access and protected states were categorized as “protected”; not protected and hostile states were categorized as “at risk of being legally limited”; and illegal states were categorized as “already legally limited.”