With contact tracing, don’t let perceptions of big tech be the enemy of the greater good

As April turns to May, the United States is preparing for another phase of the COVID-19 pandemic response: contact tracing. A public health intervention dating back to the 18th century is getting rolled out in fits and starts, often on a county by county basis and in limited cases statewide. Experts project the US will require roughly 300,000 human tracers to chart and break ongoing expansion of the pandemic. We currently have between 8,000 and 14,000. Our point of view is that the only path to success is the combination of a surge in human tracers, digital technologies to capture and share accurate and timely data with public health departments, and the will for public health entities to share this data with individuals at the community level. North Dakota and Utah are already early human and digital adopters, but we need to scale countrywide.

Big tech is stepping up to play a part. On April 10, Apple and Google announced they are partnering on a COVID-19 contact tracing platform that will enable interoperability between Android and iOS devices and Bluetooth-based contact tracing. The two have since rebranded the tool as an “exposure notification” API, but the response has still been, shall we say, strong.

Fifty-nine percent of respondents in a recent survey by the Washington Post and the University of Maryland are unwilling or unable to use contact tracing software developed by Apple and Google. Meanwhile, privacy groups have raised concerns that government monitoring during the pandemic could erode health data protections in the future. Well-respected academics have been vocal in their reactions.

“My problem with contact tracing apps is that they have absolutely no value…I’m not even talking about the privacy concerns, I mean the efficacy…this is just something governments want to do for the hell of it. To me, it’s just techies doing techie things because they don’t know what else to do.”

—Bruce Schneier, Fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Intent & Society at Harvard University

Hyperbole aside, we respectfully disagree with Mr. Schneier’s premise. Rather we feel a great urgency to arm individuals and communities seeking to “open up” with actionable information. This is the most important, and perhaps most misunderstood, action by big tech to serve the public good amidst the COVID-19 pandemic—and we can’t afford to let previous opinions or current misperceptions of the companies’ intent be the enemy of the greater good.

COVID-19 contact tracing exposes rifts in health data privacy attitudes

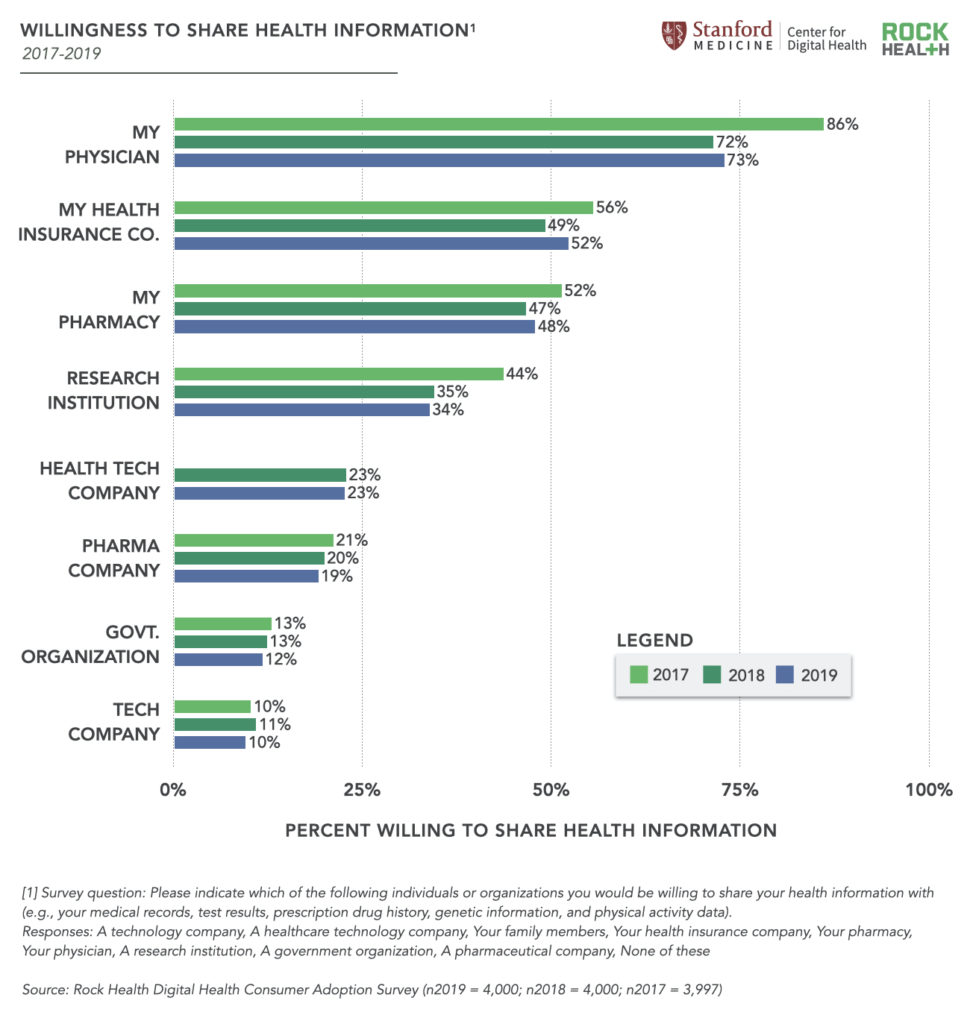

Frankly the public’s reaction to sharing data with the government and/or big tech is no surprise. Rock Health’s annual survey of 4,000 US adults consistently shows that Americans are most widely unwilling to share their health data with the government and big tech. It is no minor point of friction when the two least trusted entities are those with the resources and reach to meaningfully flatten—and hold down—the infection curve.

Countries that have successfully brought their initial surge of COVID-19 cases under control are important case studies to examine as our country prepares for the next phase of managing the outbreak. South Korea and Singapore both used a combination of digital monitoring (e.g., apps that record instances of close proximity to individuals diagnosed with COVID-19) and human contact tracers (e.g., small—or large—armies of health workers trained to track down everyone who came into contact with individuals diagnosed with COVID-19).

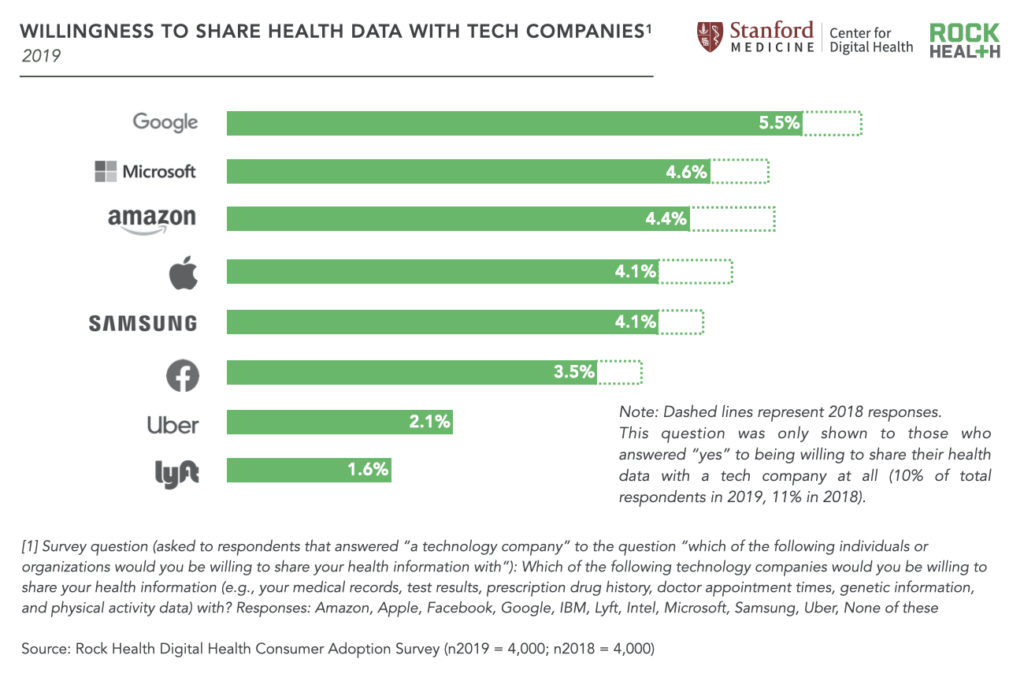

Yet despite assurances that the development environment designed by Apple and Google is privacy-preserving, suspicion of these tech behemoths abound in the US. This reaction is unsurprising—in our Consumer Adoption survey, just one in twenty respondents report willingness to share their health data with large tech companies over the past two years.

Overcoming the trust conundrum: Returning value to individuals in exchange for participation

“I don’t think the messaging about the potential for big data in healthcare has come through to the general population. If my data is shared—even in a de-identified, aggregated way—what is the individual value that’s ultimately going to be flowing back to me, and can I give consent around that?”

—Megan Zweig, Chief Operating Officer, Rock Health

To quickly overcome this techlash, we believe Apple, Google, public health leaders, and others at the forefront of the contact tracing effort must act on three fronts.

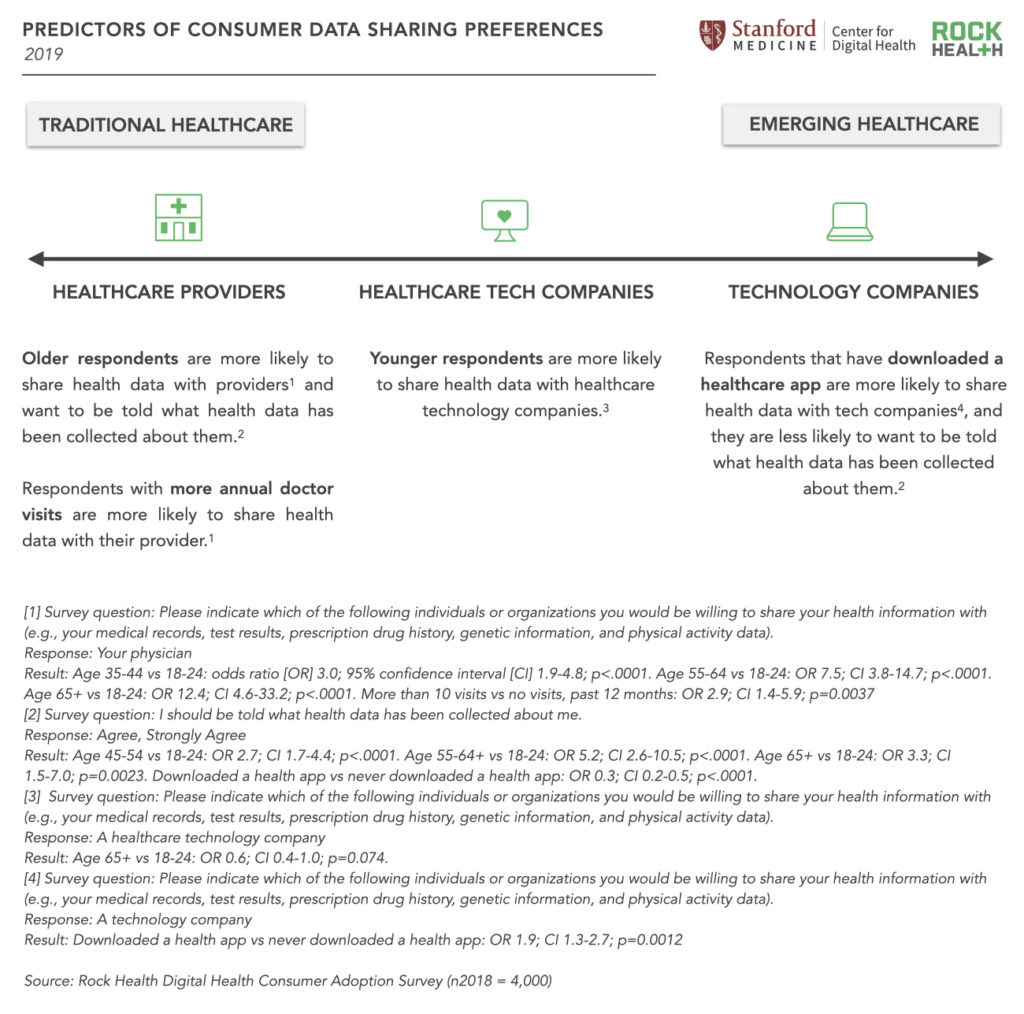

First, they must clear up the misconception that technology alone is a solution for our current needs. Technology is not equitably distributed, therefore technology-only health interventions are by definition insufficient. Even amongst those individuals who are able to access technology-only services, not everyone is willing to use them—as is made abundantly clear from our survey data above.

Second, they must embrace a multi-modal approach to who and how information is gathered. Three out of four respondents to our Consumer Adoption survey are willing to share health data with their physician, 7X more than are willing to share with a technology company or the government. Many respondents are also willing to share data with healthcare-focused technology companies—5X as many respondents would share data with a health tech company than would share with any of the FANG companies1. We know privacy concerns tend to drive adoption behavior, so any effort that excludes the trusted medical community and existing digital health brands with trusted user bases is likely to fall flat.

And third, no more time can be wasted before defining what types of data will be valued by human contact tracers and the individuals we hope will embrace DTC applications that disseminate public health information.

Contact tracers have historically done their work from call centers and with boots on the ground, working with multiple databases and applications full of inconsistencies and lacking integration (sound familiar, physicians and staff at every hospital everywhere?). Design and product teams need to observe the workflows associated with contract tracing and public health personnel to deliver digital applications that can bring real scale to operations AND integrate with other sources of data so that information can be trusted and actionable at the frontlines.

Individuals are another case entirely. So far our public health infrastructure is not getting top marks for delivering valuable information. In fact, last week one of us received a message from my physician asking if I would participate in a digital contact tracing project and I instinctively deleted the message. Looking back on that reaction I have to ask, am I hypocrite talking a big game about leveraging digital tools? Maybe not a hypocrite—just human. I’ve got zero-risk bias, loss aversion, normalcy bias, selective perception, and a whole slew of cognitive biases to deal with in the face of a vague request in what was clearly a form email. I was left wondering—what do I get for participating?

We need a really good answer to that question immediately. Instead of battling all those biases I mentioned to get to participation, we need to put our faith in good old-fashioned present bias. If you want me to opt into your contract tracing work, give me information about my community and the streets around my cul-de-sac that immediately makes me feel more informed. Understanding what information people are yearning for in a time of great uncertainty is essential to arriving at a critical mass of beacon points in our communities without a top-down enforcement policy.

The bottom line

So it turns out that, like rapid hospital capacity management in the first phase of pandemic response, success as we move to contact tracing will require a massive surge in human capital (this time in public health departments). And like physical distancing, contact tracing will require a strong measure of individuals choosing to trade aspects of their freedom for the collective good. Will we see 300,000 human tracers come out of the woodwork? That simply isn’t going to happen. Our hope is that public health departments, the federal government, and technology companies will undertake an effort to combine digital and human tracing to scale an absolutely critical task.

As another commentator recently put it, “They say there are no atheists in a foxhole, and there aren’t a lot of libertarians in a global pandemic.” We’ll see soon enough.

Footnotes

1We did not ask respondents about their willingness to share health data with Netflix, though we’d be surprised if the entertainment giant garners greater trust than its fellow FANG members.